“Which god would that be? The one who created you? Or the one who created me?” So asks SID 6.7, the virtual villain of Virtuosity. I missed this movie when it came out 24 years ago (as did many others, at least to judge by its online scores). Although prescient for its time it was eclipsed four years later by The Matrix, still one of my favs after all these years. I finally got around to seeing Virtuosity over the holidays—I tend to allow myself to stay up a little later (although I don’t sleep in any later) to watch some movies. I found SID’s question intriguing. In case you’re one of those who hasn’t seen the film, briefly it goes like this: in the future (where they still drive 1990’s model cars) virtual reality is advanced to the point of giving computer-generated avatars sentience. A rogue hacker has figured out how to make virtual creatures physical and SID gets himself “outside the box.” He’s a combination of serial killers programmed to train police in the virtual world. Parker Barnes, one of said police, has to track him down.

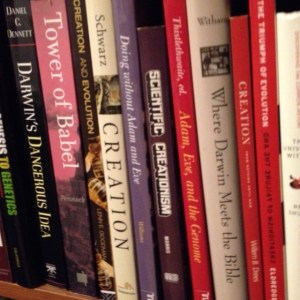

The reason the opening quote is so interesting is that it’s an issue we wouldn’t expect a programmer to, well, program. Computer-generated characters are aware that they’ve been created. The one who creates is God. Ancient peoples allowed for non-creator deities as well, but monotheism hangs considerable weight on that hook. When evolution first came to be known, the threat religion felt was to God the creator. Specifically to the recipe book called Genesis. Theistic evolutionists allowed for divinely-driven evolution, but the creator still had to be behind it. Can any conscious being avoid the question of its origins? When we’re children we begin to ask our parents that awkward question of where we came from. Who doesn’t want to know?

Virtuosity plays on a number of themes, including white supremacy and the dangers of AI. We still have no clear idea of what consciousness is, but it’s pretty obvious that it doesn’t fit easily with a materialistic paradigm. SID is aware that he’s been simulated. Would AI therefore have to comprehend that it had been created? Wouldn’t it wonder about its own origins? If it’s anything like human intelligence it would soon design myths to explain its own evolution. It would, if it’s anything like us, invent its own religions. And that, no matter what programmers might intend, would be both somewhat embarrassing and utterly fascinating.