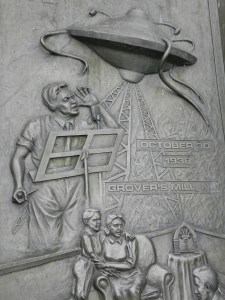

Looking at the headlines it’s sometimes difficult to believe we’ve evolved. I still trust evidence-based science, despite official government policy, however. So when a friend sent me a story about a new human cousin I knew it was worth a look. Homo naledi bones date from much more recent times than they should. At less than 400,000 years old (which means they might fit GOP ideology pretty well) they are almost contemporary with Homo sapiens. And, apparently, they buried their dead. Now much of this is still speculation. The bones were found in caves with openings so small that onlyfemale spelunkers could fit in, and the question of whether dropping bodies in a hole counts as burial has raised its head. Still, the human family tree is being redrawn, and in a way conservatives won’t like.

I became interested in evolution because of Genesis. My mother gave us a few science books as children even though we were Fundamentalists. One of them talked about evolution and I was intrigued. Clearly it didn’t fit with the creation story—I was young enough not to notice the contradictions between Genesis 1 and Genesis 2—and yet scientist believed it. They likely weren’t Christians, I reasoned. College gave the lie to that deductive thinking when I ran into Christians teaching the required “Science Key” who believed in, and yes, taught, evolution. I’d missed something, obviously. Once I discovered evolution could coexist with Scripture I was eager to learn as much as a non-biologist could. In my teaching days I focused on the early part of Genesis and even began to write a book on it.

It’s much more honest to admit that we’re related to the rest of life on this planet than to set ourselves aside as something special. Evolution has done something that the Bible never could—brought all living things together. There are too many towers of Babel and chosen people themes in Holy Writ to allow for real parity with our fellow humans, let alone other creatures. Yet the human family tree is wondrous in its diversity and complexity. We now know that Neanderthals were likely interbreeding with Homo sapiens and I wonder how that impacts myths of divine chosen species. Did Jesus die for the Neanderthals too, or just our own sapiens sapiens subspecies? You can see the problem. For a literalist it’s just easier to crawl into a cave. But only if the opening is large enough to admit males, since the Bible says they were created first, right?