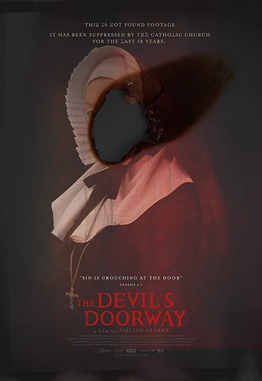

We have the basic facts, but still, it takes a good bit of imagination. We simply don’t know what the life of Mary Shelley was like, as experienced by the woman herself. The movie Mary Shelley isn’t a horror film but it’s horror adjacent. How could a movie about the woman who invented Frankenstein be anything but? The handling of Haifaa al-Mansour’s film is generally as a drama, or a romance. The story takes the angle that it was her stormy relationship with both Percy Shelley and her own father that led Mary to express her feelings of abandonment in her novel. And while we have to acknowledge the liberties all movie-makers take, it does seem interested in keeping fairly near the known details of Mary Shelley’s life. Although other women were also writing then, it was still a “man’s world” she tried to break into.

I confess that one of my reasons for wanting to see this film was that Ken Russell’s Gothic had a powerful impact on my younger mind. That movie, which is over-the-top, being the first I’d seen telling the tale, had become canonical in my mind. I know the dangers of literalism, and I wanted to see someone else’s take on the story. Al-Mansour’s treatment takes a female perspective to the narrative. It seems that Percy Shelley and Lord Byron were both advocates of what might now be termed a playboy lifestyle, and that Mary, daughter of forward thinking Mary Wollstonecraft and William Godwin, was fairly liberal herself. Although Percy Shelley, like Lord Byron, was quite famous in his time, that didn’t always equate to financial solvency. I could relate to parts of that quite well—full of creative ideas and shy on cash flow.

Mary Shelley didn’t rock the critics, but many felt it was a thoughtful treatment. It is dark and gothic, but with no real monsters. It did explain a bit of inside baseball about Ken Russell’s film. Both movies make use of Henry Fuseli’s painting The Nightmare to explore the famous meeting of Byron and the Shelleys that led to the writing of Frankenstein. Indeed, Gothic makes a good deal of it. Mary Shelley explains that Mary’s mother, Mary Wollstonecraft, had an affair with Fuseli. I was unaware of that connection. Something was clearly circulating among the Romantics, many of whom knew each other and, in their own ways, became formative of culture centuries down the road. And although many critics weren’t impressed, I think it’s about time that a woman’s point of view was brought to Mary Shelley’s life in a world not kind to women. Even if a woman gave the world one of the most influential books of the nineteenth century.