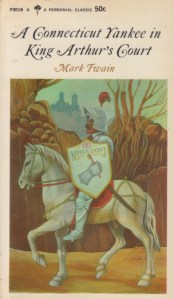

Some books stay with you in a way that hits very close to the nerve. Since I read Mark Twain’s A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court many years ago, memories of how it left me feeling prevented me from re-reading it. That’s pretty unusual for Twain, in my experience. I’ve read some of his other novels and there’s not a similar feeling toward them. The racist elements are disturbing, but overall the stories manage to overcome some of the darkness with either levity or sarcasm. The scenes that scared me off from re-reading Connecticut Yankee were the two episodes in which young women were murdered. I realize Twain was simply being honest here regarding the cheapness of life in medieval times, but I found both these instances so saddening that I had a difficult time coming back to it.

Some books stay with you in a way that hits very close to the nerve. Since I read Mark Twain’s A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court many years ago, memories of how it left me feeling prevented me from re-reading it. That’s pretty unusual for Twain, in my experience. I’ve read some of his other novels and there’s not a similar feeling toward them. The racist elements are disturbing, but overall the stories manage to overcome some of the darkness with either levity or sarcasm. The scenes that scared me off from re-reading Connecticut Yankee were the two episodes in which young women were murdered. I realize Twain was simply being honest here regarding the cheapness of life in medieval times, but I found both these instances so saddening that I had a difficult time coming back to it.

Now, some two or three decades later the book speaks to me in a new way. Something else I recently read reminded me of it, and I was struck at just how much Twain’s Arthurian peasants resemble the unthinking crowds of Americans who simply accept what people like Trump say. One of Hank Morgan’s banes is how the uneducated refuse to question what they’re told. In many ways this is humorously narrated but a dark undercurrent remains behind. Twain had clearly supposed that nineteenth-century America had overcome this brainless gullibility. A century and a half after Twain’s Connecticut Yankee we’ve clearly been involved in retrograde motion. Twain levels much of the blame on the church. His choice comments in this regard also still apply.

“I was afraid of a united Church; it makes a mighty power, the mightiest conceivable, and then when it by and by gets into selfish hands, as it is always bound to do, it means death to human liberty and paralysis to human thought.” So Morgan states in chapter 10, and indeed, in the novel it is the church that largely leads to the downfall of the civilization Morgan had built. Or again, in chapter 17: “I will say this much for the nobility: that, tyrannical, murderous, rapacious, and morally rotten as they were, they were deeply and enthusiastically religious. Nothing could divert them from the regular and faithful performance of the pieties enjoined by the Church.” Twain couldn’t admit in public, even in his own nineteenth-century life, what he really thought about organized religion. It’s pretty plain in his fiction, but disguising fact as fantasy is a tried and true method of getting at the truth. If I weren’t so sensitive to the human plight, I might read it more often.