Religion, as many a charlatan knows, makes a very good investment. History has demonstrated time and again that the confident huckster can easily siphon the money from the gullible in the name of God. What follows does not make any assertions about the character of the people involved. It is, however, a fascinating story.

Cyrus Ingerson Scofield did not have an exactly stellar career. He was raised Episcopalian (which may explain some of it), but upon being drafted into the Confederacy during the Civil War, deserted to become a lawyer in St. Louis. Scofield was forced to resign from his law post because of “questionable financial transactions” which may have included forgery. He was a heavy drinker and abandoned his wife and two daughters. The year of his divorce he remarried. Then he had a conversion experience. Conversion is the ultimate clean wiping of the slate. Any life of dissipation may be excused following a religious experience, eh, Augustine? And furthermore, in the sanctified state the motives of the former reprobate are never questioned.

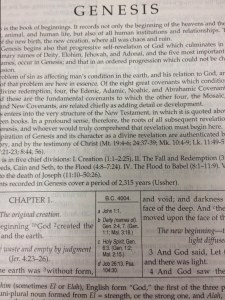

Scofield went on to join the Congregational Church and to grow wealthy from his Scofield Reference Bible, still a perennial seller, despite his lack of formal theological training. This notoriety was largely because Scofield had adopted another unlikely scheme, dispensational premillennialism. This end-time scheme grew out of the work of John Nelson Darby and later evolved into what would be called Fundamentalism. The idea was that the Bible contained an esoteric roadmap to the future, culminating in the book of Revelation, whereby the blessed could figure out exactly how the end of the world would unfold. As a child I bought a literal roadmap to the end of the world, but having survived several such putative apocalypses, I have grown a tad skeptical about the efficacy of my chart.

Any number of religious leaders have a background of self-promotion and more than a whiff of Phineas Taylor Barnum about them. A converted soul, however, is never to be questioned. Cyrus Scofield adopted Archbishop James Ussher’s dating scheme for the creation of the world in 4004 “BC” and placed it in his reference Bible, forever putting the cast of scriptural authority to a date that would come up in court cases even through the twenty-first century in Dayton, Tennessee, Little Rock, Arkansas, Dover, Pennsylvania, and Washington, DC, wasting tax-payers’ money on a myth of biblical proportions. Often creationists use “stealth candidates” who don’t exactly tell the truth before school board elections. I don’t doubt the depth of the convert’s belief, but I smell money here. And once upon a time literalists believed that it was the root of all evil.