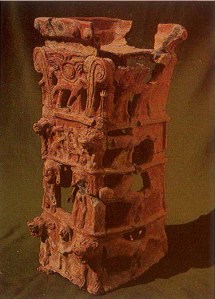

My fascination with goddesses began when I decided to research Asherah. Having grown up in a monotheistic milieu, goddesses were strangely, but not surprisingly, irrelevant. I had, of course, read about them in mythology classes, but they seemed less defined than the gods who had strong, striking characteristics. Now that I’m revisiting many classical goddesses in the course of preparing my class on Mythology, I’m discovering a renewed appreciation for the feminine divine and its contribution to the ancient world.

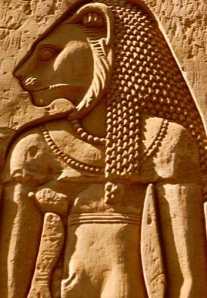

Athena and Artemis have been on my mind for the past several weeks. Among the Olympian deities they are among the strongest female figures (Aphrodite, of course, provides her own feminine form of power, and Hera, although mighty, remains largely in the background). Perhaps what creates such a striking form for Athena and Artemis is that they blend the traditional masculine and feminine roles in a way that the ancient Greeks were prescient to devise – they both possess weaponry and strength that frequently brings mortal men to their demise. They don’t wile with “feminine charms” like Aphrodite; instead they meet men on their own tuft – hunting and warfare, bravery and muscle. They are virgins, not needing male approval. Together they form the basis of many ancient aspects of divine nobility.

Today, however, when we think of Olympians Zeus and Poseidon come to mind almost immediately as the two major figures. No one disputes the unstoppable power of Zeus’ thunderbolt or Poseidon’s earthquake. The goddesses, however, display their power on the human level. They may set the fortunes of armies going to war or individuals out for personal glory or fame. They touch the characters on a more human level. They also have their counterparts, unfortunately often eclipsed, in the world of the ancient Near East. Astarte is still poorly understood, and Anat, although more fully fleshed out at Ugarit, largely remains an enigma. The importance of Athena and Artemis thus stands out in sharper relief for having survived the overly acquisitive masculine ego to remind people everywhere that goddesses also will have their due. Given enough time, perhaps even the gods will understand.