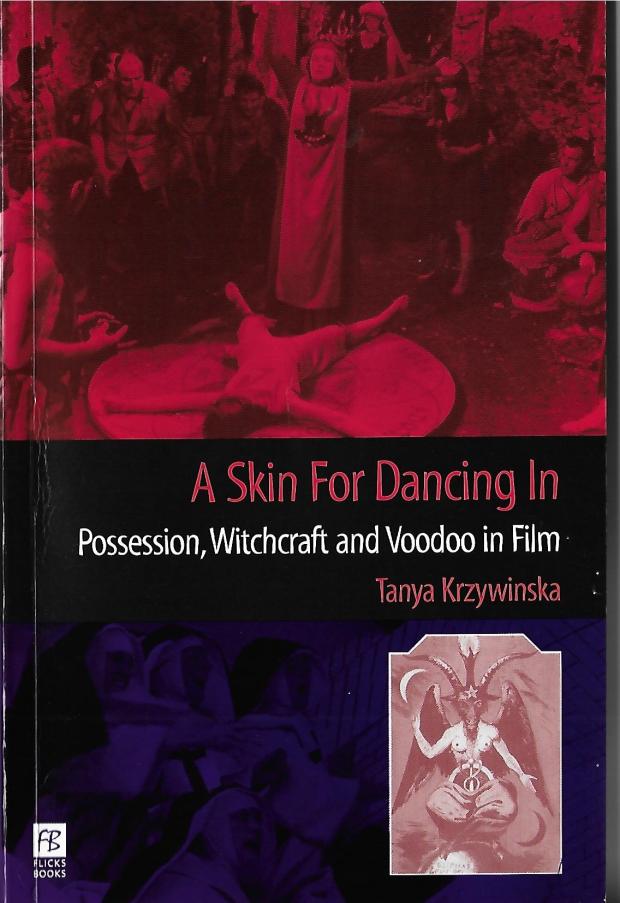

It took me back to my younger years. Tanya Krzywinska’s A Skin for Dancing In: Possession, Witchcraft and Voodoo in Film. Wide ranging and insightful, this book was a delight to read. Published in 2000, it discusses many movies that I watched in the eighties and which had somehow managed to be overrun by other stimuli since then. I like to think that, even if recall isn’t instant, that we never truly lose the books we’ve read or movies we’ve watched. (Some we may wish to forget, but that seems a sure way not to achieve that goal!) As her subtitle says, Krzywinska’s book analyzes possession, witchcraft, and voodoo. Since there are so many examples of these the discussion has to be selective, but she’s got a keen eye for choosing evocative films.

As any of my regular readers know (both of you!) I don’t really review the books in my “reviews.” I limit myself to about 500 words and I don’t like to give spoilers. A Skin for Dancing In would require quite a few words even to summarize. Krzywinska covers demonology, possession, sacrifice, paganism, witchcraft, voodoo, and more, in several movies. What really struck me in reading this was that she comes to a similar conclusion to what I’ve found—people learn about these things through film. Scholars tend not to write much about such things (although this has improved somewhat since the turn of the millennium). The average person doesn’t read academic books, and since culture has become “rational” there’s not much talk about such things from discoursing heads. Still, movies.

These topics make for great movies. One of the points I’ve made in my own work is that what we know about demons comes from the cinema. It seems that we should pay close attention to what movies tell us. They’re the “public intellectuals” that many academics want to be. A Skin for Dancing In is a good example—it’s compelling, if a little academic, but very hard to find. It’s difficult to lead public discussion if your book is limited to university libraries and those who have access to them. Of course, you don’t need a talented scholar to tell you how to watch a movie, but I was reminded here of many films I thought I had forgotten. And what’s more, I have a deeper understanding of how they fit into the larger world of cinematic possession. This is one of those books I wish I’d found sooner.