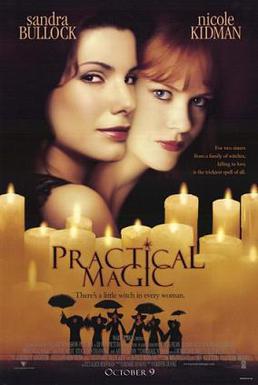

October means different things to different people. I know what it feels like to me and I suspect, and hope, that there are others who experience it like I do. When I search for October movies I’m looking for a kind of happy melancholy unique to the season, but others seem to think movies about witches capture the feel. So it was that I came to watch Practical Magic, which was recommended on more than one October movie list. It’s not a horror film, in fact it’s a rom-com and it doesn’t try to frighten anyone, although there is one tense scene. Like many movies about modern-day witches, it has a good message of female empowerment. I’m glad I watched it for that reason, and the story isn’t bad. Set on an island community, presumably in Massachusetts, but shot in California, it’s not exactly falling leaves and pumpkins, though.

Witches seem to be the preferred monsters for feminine endorsement. Most people, I suspect, wish they had magical powers. We all want things to go our way and would like to manipulate them in that direction. But there’s something more to it. It’s tapping into an ultimate power—something that can’t be challenged. Practical Magic, although not always in a serious mood, does portray the struggles witches have against occult powers. The story is of the Owens family, which have been witches since the pilgrims landed. They suffer under a curse dooming the men with whom they fall in love. Not all the women are cut out for such a life. So it is that Gillian and Sally set out to break the curse, each in their own way.

Other occult powers are at work, however. One is clearly the curse itself and another seems to be an undead boyfriend who eventually possesses Gillian. The women of the community have to come together to exorcise this entity, and that finally leads to communal acceptance of witches. A major studio production with a reasonable budget and star power, it really didn’t do well at the box office. Barbie seems to have struck a feminist chord that Practical Magic was reaching for, but the late nineties were a time when women’s power seemed to be starting to secure itself. I noticed that, when looking for the movie on streaming services, it’s now having a limited theatrical run—it’s October, after all. This may not be my October movie, but it has a good message that still needs to be learned.