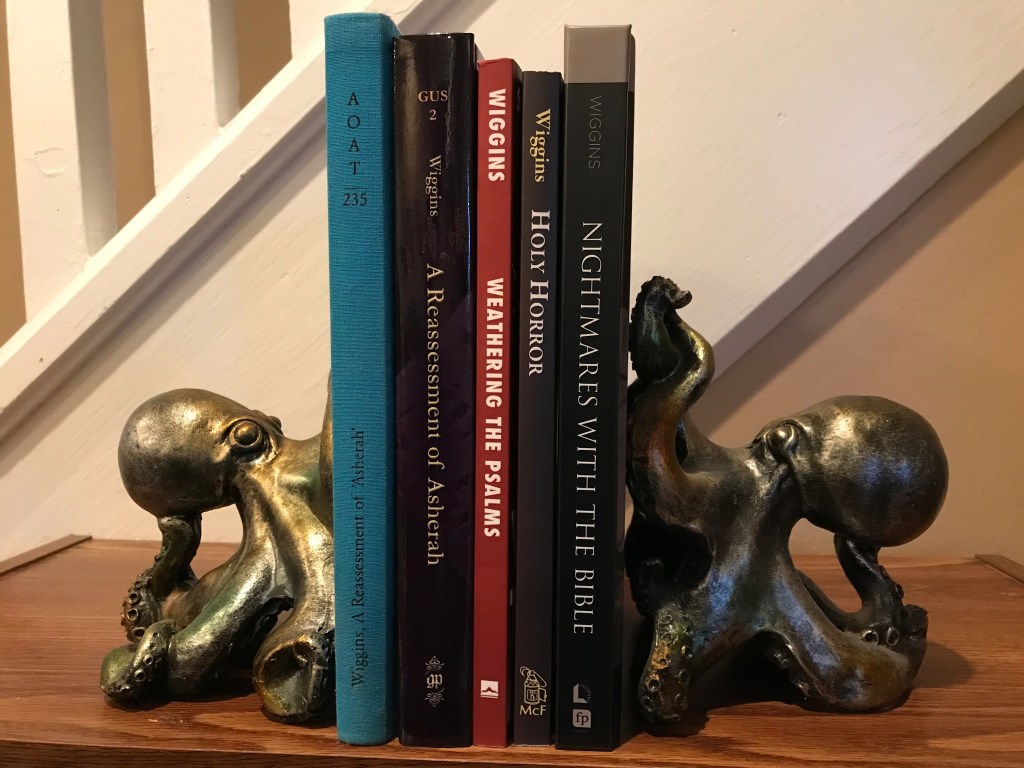

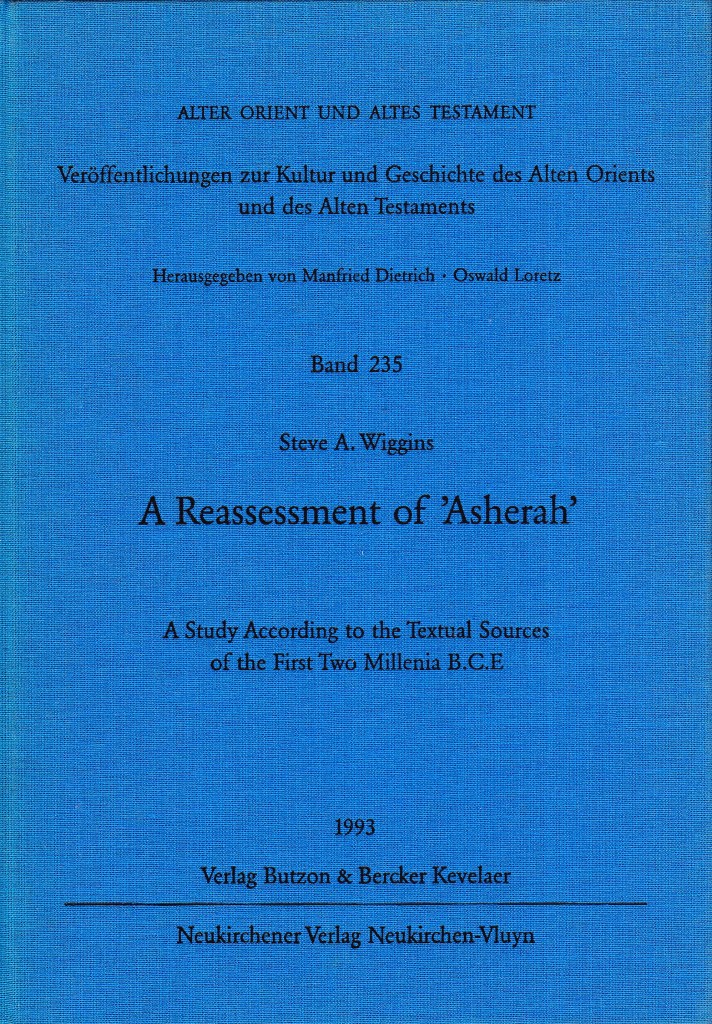

Under-printing, ironically, can create great demand. Books are generally under-printed because publishers don’t see much of a market for them. Back before the days of inexpensive print-on-demand (POD, in the lingo) books may not have even existed as electronic files. Often a publisher won’t print a book unless it anticipates that it can make back its costs. If they think it won’t sell that well, they’ll print just enough. And they might even melt down the typeset plates to reuse them for other books. I’m not sure if that happened in the case of a book I’ve been looking to consult, but something has made this under-printed book extremely rare. It’s not on Internet Archive. WorldCat shows it in only two libraries world-wide, the nearest one over 3,000 miles away. Its price used (and there seems to be only one copy) is $46,000. I can’t tell you what it is because you might buy it before I can.

For the purposes of my research, this is actually the only book on this particular topic. (The subject isn’t even that obscure.) The book is cited everywhere this topic is mentioned, and at least one person on Goodreads has actually seen a copy of it. I have to conclude that all those who cite it must live within driving distance of one of two libraries worldwide. For the rest of us the book is simply inaccessible. As an author this is one of the worst fates imaginable. Even if some price-gouger is selling a copy for $46,000 the author gains nothing from it. Royalties are null and void for used book sales. The only profiteer is the person who happens to have found a rare book (from the 1990s!) and is determined to ensure only the most wealthy will be able to purchase it.

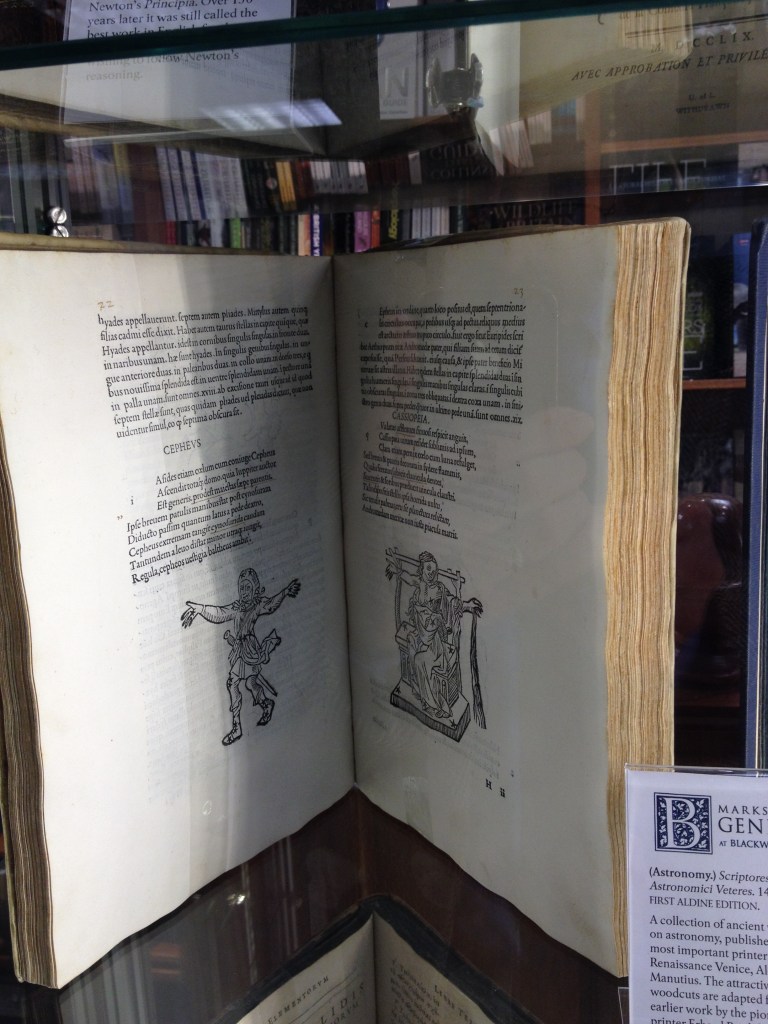

I’ve known people who sell used books online. Those who want to move books try to undersell the unfortunate under-printed title by pricing a bit lower than the competition. There is no regulation, however. You can charge whatever you like. The funny thing is, if someone eventually forks over $46,000 for this book, and then has it appraised (it is a paperback from the 1990s), its actual worth is probably at most in the hundreds of dollars. Back when we watched the Antiques Roadshow we always knew that the poor person who brought in a book would be disappointed in the appraisal. Last time I was in Oxford I saw rare books from the 1400s for sale for far, far less than $46,000. I only hope that my books, as obscure as they are, are never deemed that expensive. And I would encourage publishers to print a bit more generously, for the sake of knowledge.