I thought this was over after school. Sitting in a class with a long list of names, always coming in last—or very nearly so—because my name began with W. Even now, however, it still happens at work. If there are a limited number of places at an event, just try to register with a W (or X, Y, or Z) name. Even if you get your name in first, you automatically drop to the bottom of the stack for many electronic lists (AI knows the alphabet, right Hal?). This got me to thinking about the alphabet. Alphabetical order is, of course, neither fair nor random. It follows strict rules and it must in order to work properly. The assignment of alphabetical order, however, is arbitrary. More than that, it is a teaching tool cum organizing principle.

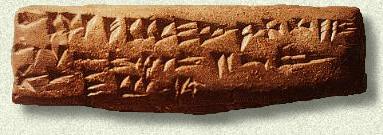

Consider your basic keyboard. It’s used far more often than the alphabet and if we went in QWERTY order, Ws would always be near the front of the list. Problem is, although our fingers know the keyboard well, who can recite it? Maybe we need a mnemonic device like “Quite well, early riser, thank you…” Someone at some stage laid out alphabetic order. The earliest known abecedaries seem to come from Ugarit. That doesn’t mean they were invented there, but it also doesn’t mean they couldn’t have been. We don’t know what the criteria were, but interestingly enough, what we transliterate as w came about sixth place. The order is largely recognizable to modern schoolchildren, although they had fewer letters and some of them we don’t have. W was in the middle but closer to the head of the class.

There have likely been psychological studies done on the mental state inflicted by always being last, or near the end. Granted, a good part of it is because of the gospels, but I wonder if my tendency to think others should go in front of me is a life-long socialization of being a W. Growing up in a town with few “exotic” names, I don’t recall ever not being last. There were teachers who would divide by height, but that’s even worse because I’m not tall. Could it be that something as random as scratch marks made on clay by some priest or scribe in illo tempore, thousands of years ago, led to such a blog post as this in the early twenty-first century? All I know is that my projects at work still get bumped because kindergarten politics still hold.