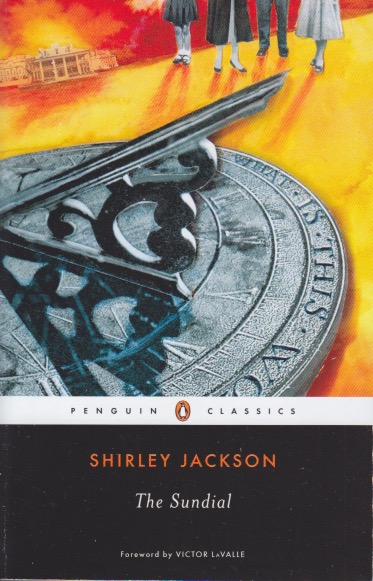

Although I have many authors I like to read, I haven’t fully explored the oeuvre of many. I’m an eclectic reader and I’m also often limited by bookstores as to what I pick up. I’ve read Shirley Jackson’s two biggest successes, The Haunting of Hill House and We Have Always Lived in the Castle, as well as her famous short story, “The Lottery.” I knew she had written much else, but I couldn’t really tell you what. When I go into a small, independent bookstore I hate to leave with nothing, and seeing Jackson’s The Sundial on the shelf, I decided to give it a try. In some ways it was quite a departure from her usual style in that it is openly humorous. Nevertheless, it’s clear that this is the same thinker who gave us the Castle.

Plotwise, the story is about anticipating the end of the world. The Halloran family lives in a large mansion on the money made by the original patriarch, but is beset by interpersonal issues. A wealthy family, there are at least three contenders for control of the fortune. When one of the family members has a premonition about the end of the world, they come to believe it and prepare for the event with personality quirks becoming more and more pronounced as they realize the only people that are going to be left to judge them will be themselves. Various guests stop by and the matriarch decides on who might stay, and survive, and who must go. A group of twelve, including two domestics, is finally settled upon.

As with all Jackson novels, there are layers here. Things to think about. One of the funny scenarios involves the goodhearted maid—perhaps the most innocent of all the survivors—revealing to a local villager what’s about to happen. Not believing her, he refers her to a group of religious believers that have come to a similar conclusion. This leads to a meeting between the matriarch of the Halloran family and the leaders of the religious group. Not surprisingly, it turns out that their versions of the end of all things are different, and Mrs. Halloran turns them away since she can’t relinquish her secular beliefs about the matter. As the time grows closer, the reader is drawn in by the conviction of those in the house. Their isolation and reflections on life with no other people beyond themselves grows in intensity. After putting the book down a sense of doom lingers. And that, it seems, is what Shirley Jackson is very capable of doing, even if in a comedic gothic setting.