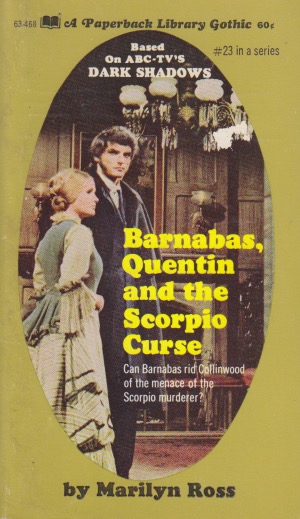

It must be difficult to write the same basic story over and over. And nostalgic adults like me can be tough critics as we try to recapture faded childhood glories. Those memories fade like afternoon shading into evening, but still I can’t help myself. Marilyn Ross wrote 33 gothic tales of Dark Shadows in the spinoff series from the long-running television program, and I’m determined to read them all. In small doses. The one, Barnabas, Quentin and the Serpent is actually a bit distinct. The writing is still journeyman, that of a tired potboiler author, but the plot offers something a little different. As in the last volume reviewed, Barnabas is free from the vampire curse for a time, allowing him to emerge in the daylight. And his arrival at Collinwood is actually dramatic and well-timed. The story is set in the nineteenth century.

Gerald Collins, a professor of archaeology, unexpectedly inherits Collinwood along with his daughter Irma. They head to Maine from Mexico taking exotic creatures with them, including a dimetrodon that escapes and tries to eat them. The story revolves around rumors that the professor caught and transported back a flying serpent. At Collinwood (and let’s think about this a minute—if you add up the body count from all the novels you’ve got to wonder why there’s been no federal investigation) people start to die and reports circulate of a flying snake. The professor’s going to be driven out of town because angry villagers think he brought this creature back with him. It’s all very melodramatic.

As in the last novel, Barnabas acts as a detective. Quentin, who is the werewolf cousin, manages to allude detection by disguising himself. Even Barnabas is fooled. The story tries to avoid invoking the supernatural—there’s no such thing as flying serpents—while allowing a werewolf to perpetrate a hoax. It’s all good fun (except for that body count). There’s a bit of vim here from our weary journeyman writer, but there are nine novels yet to go in the series. Writing a series seems to be smart money. Children (and I first read several volumes of this series as a child) like to complete things and can be loyal series fans. I never read the full series when I was younger; they were haphazard finds at the local Goodwill book bin. Of course they were still being published at that time. I have to admit that I’m curious where it will go from here. And I do miss Barnabas as a vampire.