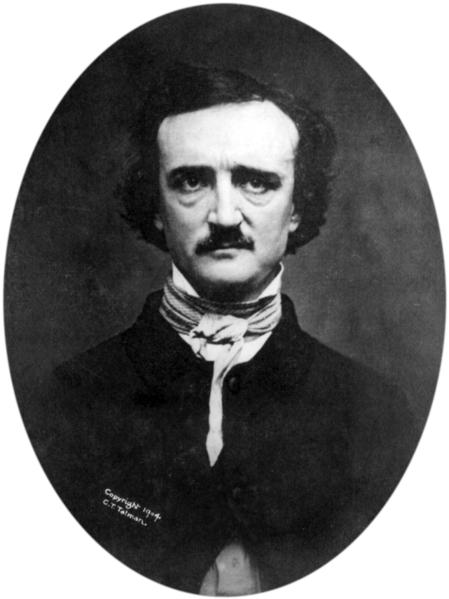

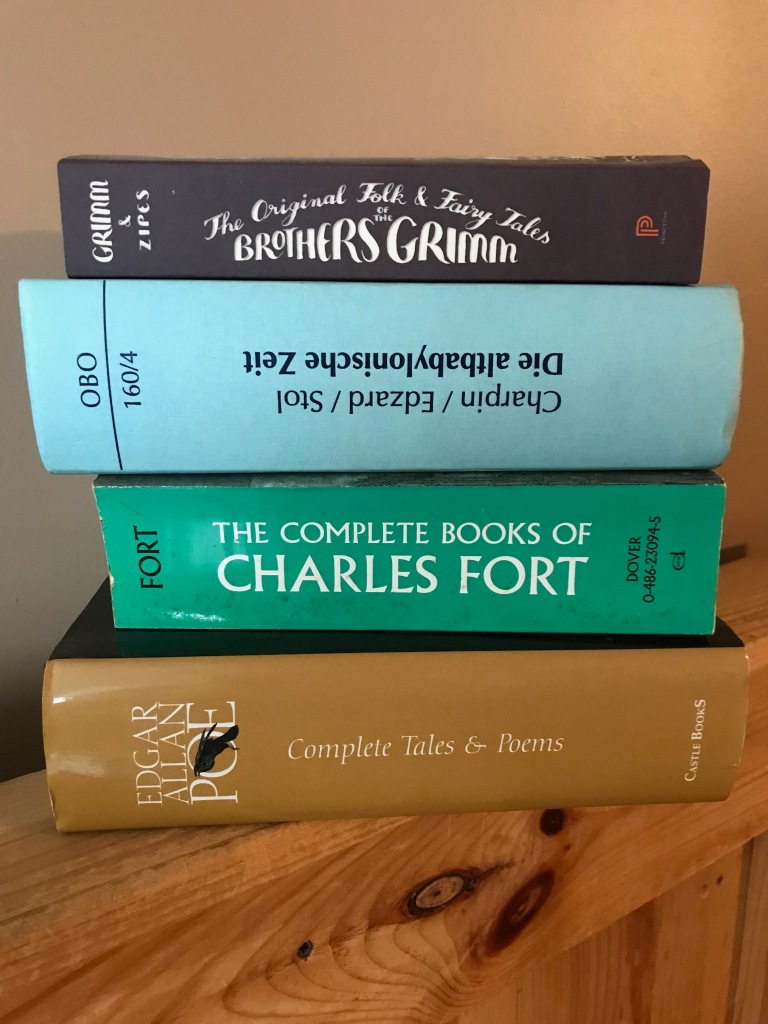

A gift a friend gave me started me on an adventure. The gift was a nice edition of Poe stories. It’s divided up according to different collections, one being Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque. This was originally the title of a collection of 25 stories selected by Poe himself in 1840. I realized that much of my exposure to Poe was through collections selected by others such as Tales of Mystery and Terror, never published by Poe in that form. I was curious to see what Poe himself saw as belonging together. I write short stories and I’ve sent collections off several times, but with no success at getting them published. I know, however, what it feels like to compile my own work and the impact that I hope it might have (if it ever gets published). Now finding a complete edition of Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque turned out to be more difficult than expected.

Amazon has copies, of course. They are apparently all printed from a master PDF somewhere since they’re all missing one of the stories. The second-to-last tale, “The Visionary,” is missing. I searched many editions, using the “read sample” feature on Amazon. They all default to the Kindle edition with the missing tale. I even looked elsewhere (gasp!) and found that an edition published in 1980 contained all the stories. I put its ISBN in Amazon’s system and the “read sample” button pulled up the same faulty PDF. Considerable searching led me to a website that actually listed the full contents of the 1980 edition I’d searched out, and I discovered that, contrary to Amazon, the missing piece was there. I tried to use ratiocination to figure it out.

I suspect that someone, back when ebooks became easy to make, hurried put together a copy of Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque. They missed a piece, never stopping to count because Poe’s preface says “25” tales are included, but there were only 24. Other hawkers (anyone may print and sell material in the public domain, and even AI can do it) simply made copies of the original faulty file and sold their own editions. Amazon, assuming that the same title by the same author will have the same contents, and wishing to drive everyone to ebooks (specifically Kindle), offers its own version of what it thinks is the full content of the book. This is more than buyer beware. This is a snapshot of what our future looks like when AI takes over. I ordered a used print copy of the original edition with the missing story. At least when the AI apocalypse takes place I’ll have something to read.