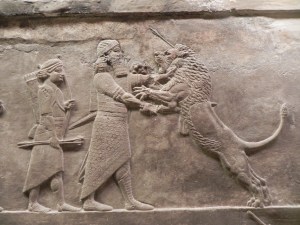

In a recent post on BBC Health, James Gallagher discusses ancient Assyria. What can ancient Assyria have to say about modern health, beyond the occasional liver model used in haruspicy? Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, of course. As Gallagher notes in his article, PTSD was diagnosed after the Vietnam War. That doesn’t mean it wasn’t in existence long before then. In fact, it stands to reason that if people experience it now, they likely experienced it during traumatic events then. War is among the most horrific and tragic activities in which humanity engages. Men, in the days of Assyria, sent to kill other men in the hundreds, and thousands, could not have walked away from the battlefield unchanged. There are those who seem not to suffer, but the majority of us know that, no matter how just the cause, it is simply wrong to kill others. On a massive scale it can only be worse.

Multiple stresses, I would contend, go undiagnosed. I have known those who’ve experienced significant loss—a job, for example, in an economy that makes future prospects dim—who begin showing the same kinds of symptoms. They are, of course, not diagnosed with PTSD, but are simply told to either buck up or go see a shrink. “Pull up your socks,” as they say in the UK. I wonder, though, if it is that simple. People throughout history have been capable of inflicting great stress on one another. Sometimes it becomes so normal that we don’t even recognize it. The forcing of loss and resultant terror of future deprivation is a daily affair. The civilization we’ve been is so complex almost to demand this kind of horror. We may not be sent to the battlefield to kill others, but we are daily faced with situations that cause us great pain, often for prolonged periods. And we wonder why people aren’t satisfied.

Please don’t misunderstand me. I have no doubt that the level of stress faced by those who survive war is severe. I don’t make light of it. Being a pacifist, I do believe there is a solution to war that involves education instead of fighting, but I don’t in any way suggest that those who suffer aren’t suffering in reality. They are. Sometimes they can no longer function in society. We institutionalize, cut funds, then send them out on the streets. This is nothing new. As Gallagher points out, soldiers in antiquity weren’t professionals. All healthy men, apart from the one-percenters of the day, served in armies on a rotating basis. One thing, however, has not changed over the millennia. War today remains as unnecessary as it was then. If we could turn our attention to improving the lot of the 99 lost sheep, the one already found might, to its surprise, be much better off if all were accorded ample care.