I used to be afraid of them. The band Black Sabbath, I mean. I heard the songs from Paranoid wafting from my older brother’s room (separated from mine by only a curtain) and was secretly intrigued. But the name of the band—wasn’t that satanic? To a young Fundamentalist there was much to fear in the world. More than once I bought Alice Cooper’s Welcome to My Nightmare only to replace the copy I’d thrown away in evangelical terror. I recently learned, however, the the band name Black Sabbath was taken from a 1963 horror movie. And I also learned that the film was, in part, based on a Russian vampire story by Leo Tolstoy’s second cousin Alexei, titled The Family of the Vourdalak. And that this story was published decades after Tolstoy’s flop, The Vampire. That novel was inspired, in turn, by John Polidori’s The Vampyre.

Polidori’s work was inspired by a fragment by Lord Byron, which he contributed to the ghost stories putatively told among friends a stormy night in Geneva that also led to Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. Connections such as this are immensely satisfying to me. Although I taught mainly biblical studies, my training was in the history of religions—it just happened to focus on ancient semitic examples. Finding the history of an idea is one of the great pleasures of life. But we’ve left Black Sabbath hanging, haven’t we? The band realized something that Cooper would run with, namely, horror themed songs and metal go naturally together. Such dark things led evangelicals to condemn the whole enterprise, claiming the band name was satanically inspired. (Michael Jackson, raised as a Jehovah’s Witness, was famously fond of horror, although Thriller is perhaps the least scary horror-inspired album ever.)

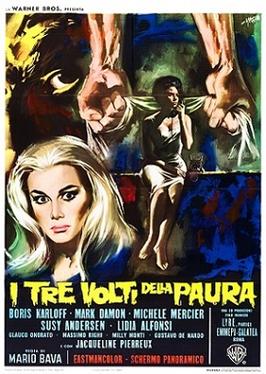

I’d never seen Black Sabbath before, so now I had to watch it. Of course, there’s nothing satanic about it. An Italian, French, American collaboration, it’s a set of three stories bound together by Boris Karloff’s narration, and it’s all in Italian. One story is about a woman double-crossed but saved by an estranged friend. The second, the one featuring Karloff, is the one based on Alexei Tolstoy’s Russian vampire tale. The third is about a poor woman who steals from a dead patron and is haunted until the inevitable happens. Not particularly scary, the film title was the inspiration for the band, not the content. They were therefore labelled satanic because of a movie that has nothing to do with satanism. The song “Black Sabbath” was actually inspired by Dennis Wheatley novels, which do, of course, deal with satanism. The song itself isn’t satanic. They decided to make songs like horror films in music. And it all goes back to Lord Byron and the night near Geneva that inspired both Frankenstein and Dracula.