You just never know. A few months back I emailed Liverpool University Press because my book, The Wicker Man, has apparently not sold any copies. I had never received (have still never received) a royalty statement or any payment. Now, I’m willing to accept that no copies have sold. I’m not a recognized name and a bigger book came out in 2023, the fiftieth anniversary of the film. I moved on. Then, the day before my Sleepy Hollow as American Myth copies were scheduled to arrive, a friend sent me a text that made my day. He’d seen on the MIT bookstore staff picks shelf, a copy of my humble little book. I was floored. Someone had read it and liked it. And MIT! I mean, that’s worth celebrating. It also made me curious.

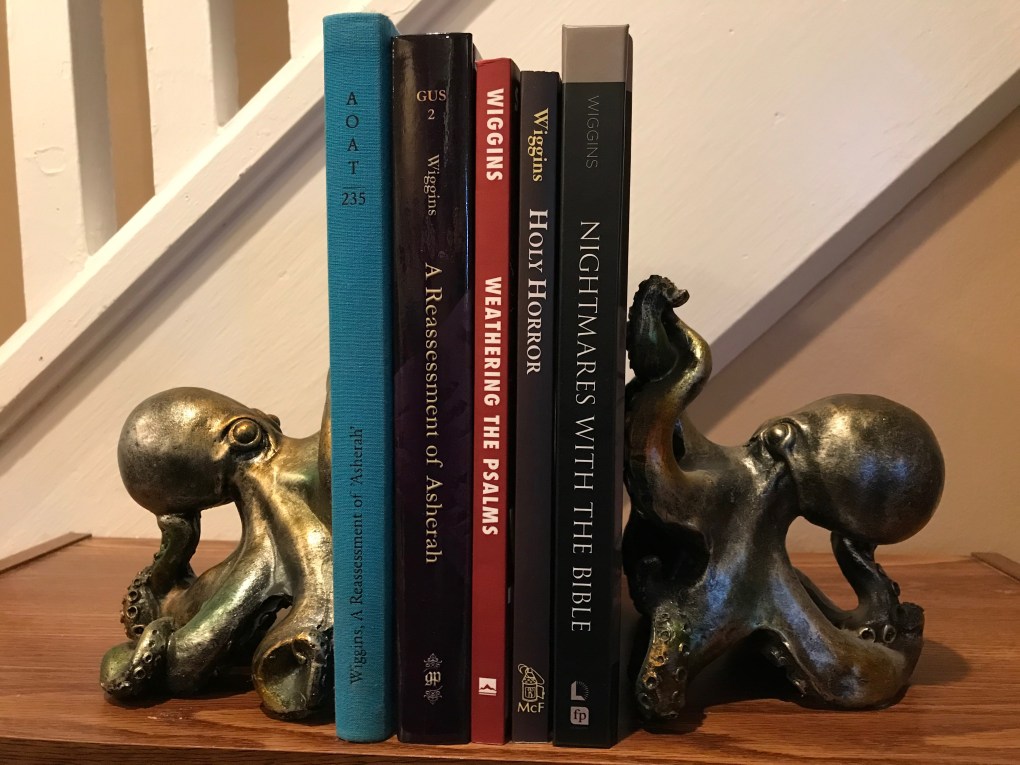

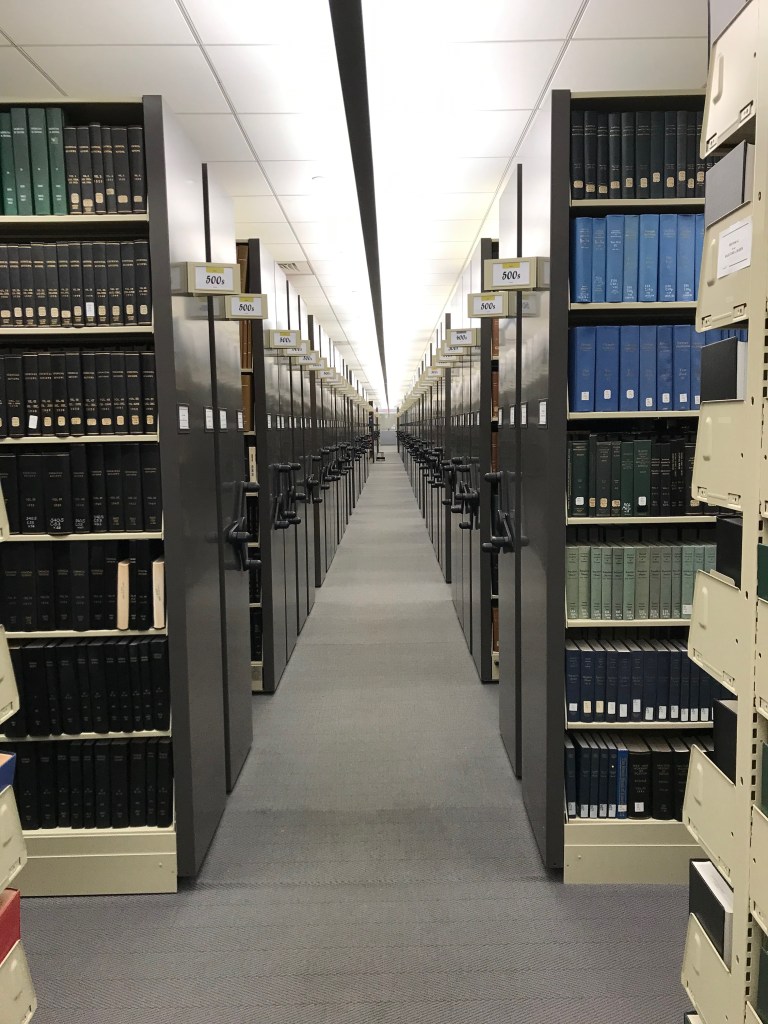

I checked a website that tracks classroom adoptions. The Wicker Man had been adopted for a class at Kennesaw State University in Georgia. Ironically, just the day before my friend’s text arrived, a colleague at a nearby seminary asked if I’d come and give a talk about Weathering the Psalms. This is all very dizzying to me. I am an obscure private intellectual because no schools will open resident scholar or any other such non-tenure positions to me. I can’t even verify myself on Google Scholar. But a few people, it seems, have found my books. In case you might think otherwise, I’m very well aware that the scholarly world is small (and the current administration would like to make it smaller by the day). But I tend to think of myself as lost in that small world.

The Wicker Man was a departure for me, as is Sleepy Hollow as American Myth. In these two books I moved away from my identity as a scholar of religion. Don’t get me wrong, I’ve used my background and experience, and even latent knowledge of religious studies in both books, but they aren’t fronting religion. It remains to be seen if the just curious will pick them up. I know many people don’t default to, “I find this interesting, I’ll buy a book on it,” as I do. And I’m more than willing to suppose that others aren’t interested in what I have to say. Still, just when I’m starting to feel down on all my efforts, a little ray of hope shines through. Someone in a bookstore somewhere has recommended one of my books. And it feels good.