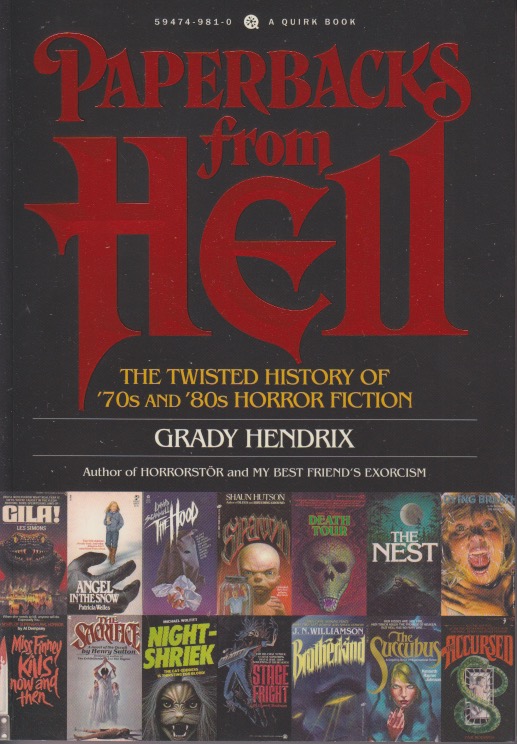

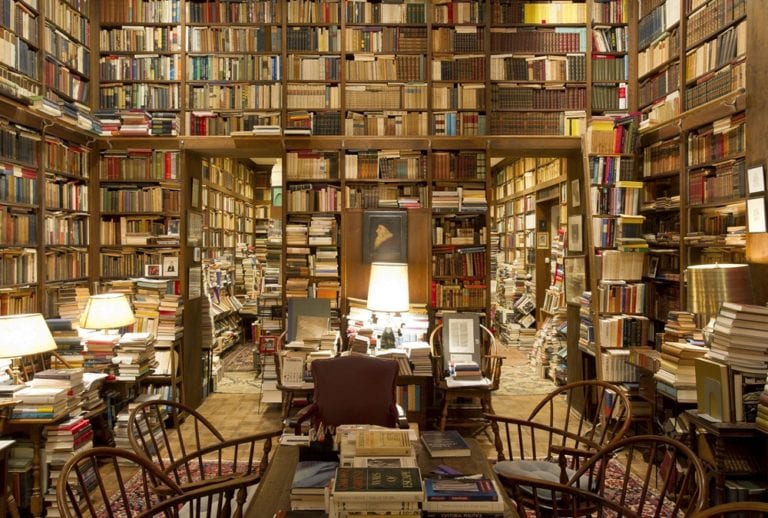

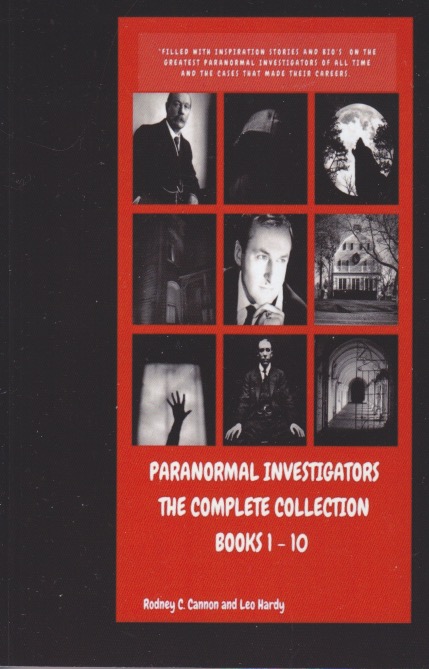

Sometimes I wonder why I do it. Horror is a strange category for books and films, but one thing that may be a draw is that they take me back. Life, it seems, is cyclical. I liked monsters as a kid, and grew out of it when college and graduate school taught me to be serious. As a working academic this genre can spell death to your career, so when my career died anyway, I was left grasping at my childhood to try to make any sense of this. Grady Hendrix’s Paperbacks from Hell took me back. Not that I’ve read all the books listed here—I came away with a list I want to read—but the lurid covers are a reminder of the kinds of things that caught my young imagination.

Subtitled The Twisted History of ‘70s and ‘80s Horror Fiction, this is actually a very fun book to read. Hendrix has a light touch and had me nearly laughing out loud (quite an accomplishment) a time or two. And I learned a lot. Although I write books about horror, the genre is a large and sprawling one and this book takes a clear focus at the paperback market. Just a reminder: paperback originals were designed to be sold and consumed quickly. No waiting around for 18 months while profits from the hardcover roll in. Hendrix really knows what he’s talking about when it comes to the history. It also seems like he may have read more horror than is necessarily good for you. He clearly knows how the publishing business works.

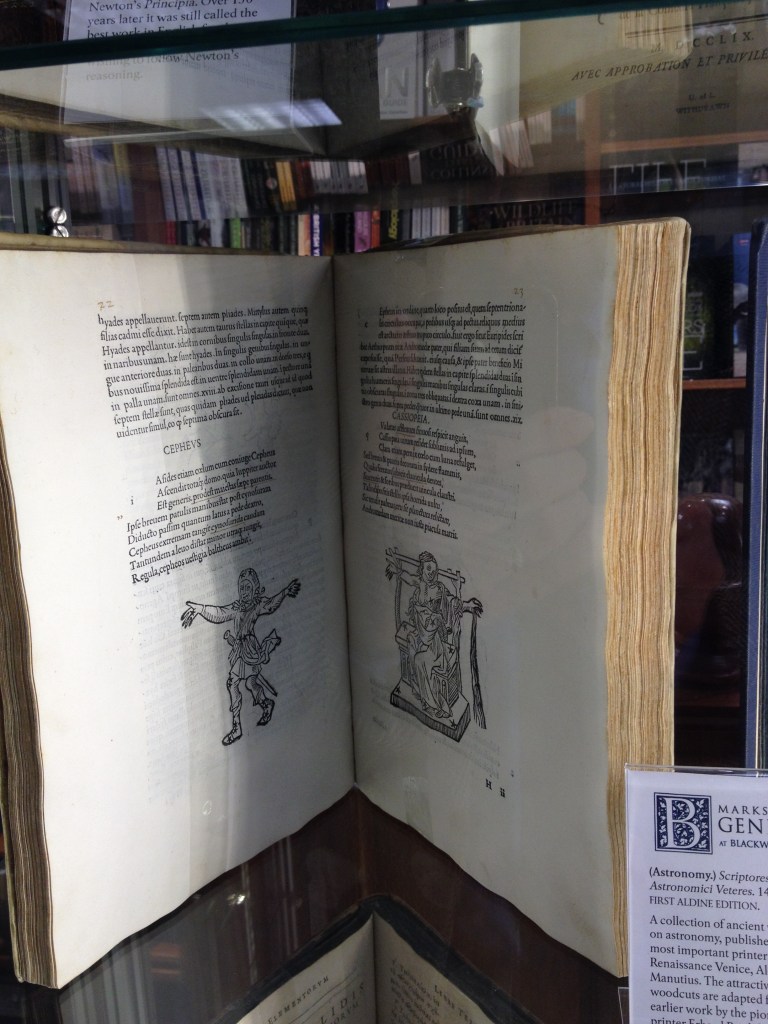

Several of these books were big enough that I knew about them. He starts off with Rosemary’s Baby and The Exorcist. (And The Other, which I’m now obligated to find and read.) In fact, the first chapter focuses on religion-themed horror. This is something that only began in earnest in the late ‘60s. While the horror paperback market may have tanked in the ‘90s, the film side of the genre has been doing quite well and continues to do so. The late sixties also got that kick-started. It seems that when people stopped running from the fact that religion is scary, horror itself grew up. I was shielded from that part as a child, but now, looking back, I can see that things weren’t quite what they seemed. This full-color, grotesquely illustrated book has great curb appeal. And if you’re not careful, you can learn a thing or two as well.