A friend keenly aware of my interest in the unusual sent me a story about the “Devil’s Footprints” that sometimes occur in snow. The article focuses on an instance in England in 1855 but which was reprised in 2009. The prints, made by a bipedal, cloven-hoofed animal, surmount tall barriers and occur on rooftops as well as on the ground. Such a phenomena is not limited to England. Associated with the Jersey Devil, similar unusual trails were reported during the flap of sightings in the early part of the last century here in New Jersey. As the piece on Mental Floss states, this is most assuredly not diabolical work, but it does make me wonder why people associate the unknown with the Devil.

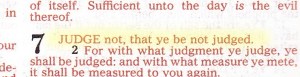

As a character in world religions, the Devil can trace his (and, like God, he is almost always a male) origins to the Zoroastrians. Zoroastrian theology is a dualistic outlook: ultimate good versus ultimate evil, Good God versus Bad God. The idea synced particularly well with the burgeoning of apocalyptic thought that hovered in the air during the time that the people of ancient Judah came into contact with Persian thinking. The idea was toned down, of course, to a being with lesser powers than God, but still a real foe with which to contend. By the time of the New Testament, the Devil was ensconced and associated with the Persian accuser known by the title of “the Satan,” or the divine prosecuting attorney. How this character came to be associated with strange footprints in the snow traces an odd trail indeed. The key is the cloven hooves.

No description of the Devil exists in the Bible. The best evidence suggests that the horns, goatish bottom, and cloven hooves come from an association with the Greek demigod Pan. Why Pan was singled out as a particularly bad god is not known. He was popular in ancient Greece. It is certain that the Jews of Jesus’ time would not have recognized a cloven hoofed beast as devilish. The livelihood of too many relied on sheep and goats. Once the transformation took place in the imagination, unexplained cloven footprints appearing in the night suddenly became those of the Devil. As Stacy Conradt points out in her Mental Floss post, several suggestions have been made for creatures of the natural world and their snowy markers. We don’t know what makes the footprints, however, and winter is all the richer for it.