It was bound to happen sooner or later. I married into a family of singers, and when we gather at a cabin in the woods, singing breaks out. In the drought-tormented northwest, under an extreme fire ban, there was no campfire, but that doesn’t stop the music. Once campfire songs begin, “Green Grow the Rushes, O,” always appears. I’m no singer, but I spent a couple years as a camp counselor, and many years before that as a youth conference attendee in the United Methodist Church. I know the song by heart. Usually it is now a sign for the adult males to sneak back to the cabin rather than endure the twelve repeating verses. Nevertheless, the question invariably comes up: what do the words mean? We have a couple of lists, here and there, explaining the lyrics, but the fact is the origins and meaning of the carol are obscure. It’s origins appear to be England, but the countdown of twelve verses contain imagery that is Christian, Jewish, and pagan. Over time, many of the verses have, like most oral tradition, undergone corruption. In many respects, it is almost biblical.

While it might be fun to run down all the verses and discuss their potential meaning, that is a task best left to a day when I have my computer working again. With limited internet access and an iPhone from which to post, full-scale exegesis is a daunting task. One aspect of the song, in any case, is clear—it is generally accepted to be a Christian catechetical tool. Repetitive and, especially before adulthood, fun, the song rewards those with strong memories for such obscure phrases as “April rainers,” “symbols at your door,” and “bright shiners,” in the proper order. After the song is over the teaching begins.

I have a book of camp songs from my counseling days, and it suggests a hermeneutic key to the song. My wife studied musicology, and she provided a somewhat more authoritative source. Then, of course, there’s Wikipedia. On some of the verses there is a general consensus, but most are open for debate, with some seeming to point to pagan origins. Tied up with the fact that the song is, in some places, connected with Christmas, this blend of Jewish, pagan, and Christian ideas comes as no surprise. The age and origins of the song are unknown, but it features references to Greek deities, Jewish laws, and Christian miracle stories. Musicologists have had a crack at the song, and surely will examine it again. The strangeness of the lyrics suggest a mystery to explore. Some mysteries are still to be found around the campfires of the north woods on a summer’s night.

Monster Impulse

Some people are impulse buyers. In fact, retailers count on it. All those last-minute items next to the cash register while you wait your turn to consume—they beckon the unwary. I have to admit to being an impulse book buyer. I have to keep it under control, of course, since books are “durable goods” and last more than a single lifetime, with any luck at all. A few years ago I was in the shop of the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh. It was my last day in the city where I’d spent my post-graduate years and I didn’t know when I’d ever be back. What could help me remember this visit? A book, of course. Why I chose Monsters, by Christopher Dell, to mark this particular occasion, I don’t know. I love monsters, yes, but why here? Why now? Why in the last hours I had in my favorite European city? It was a heavy book, hardcover and unyielding in my luggage. I had to have it.

Some people are impulse buyers. In fact, retailers count on it. All those last-minute items next to the cash register while you wait your turn to consume—they beckon the unwary. I have to admit to being an impulse book buyer. I have to keep it under control, of course, since books are “durable goods” and last more than a single lifetime, with any luck at all. A few years ago I was in the shop of the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh. It was my last day in the city where I’d spent my post-graduate years and I didn’t know when I’d ever be back. What could help me remember this visit? A book, of course. Why I chose Monsters, by Christopher Dell, to mark this particular occasion, I don’t know. I love monsters, yes, but why here? Why now? Why in the last hours I had in my favorite European city? It was a heavy book, hardcover and unyielding in my luggage. I had to have it.

More of an extended essay than a narrative book, Dell’s Monsters begins with a premise that I never tire of contemplating: religions give us our monsters. At least historically, they have. There is an element of the divine as well as the diabolical in the world of monsters. As a student of art, what Dell has put together in this book is a full-color unlikely bestiary. These are the creatures that have haunted our imaginations since people began to draw, and probably before. One exception I would take to Dell’s narrative is that the Bible does have its share of monsters. He mentions Leviathan, Behemoth, and the beast of Revelation, but the Bible is populated with the bizarre and weird. Nebuchadnezzar becomes a monster. Demons caper through the New Testament. The Bible opens with a talking serpent. These may not be the monsters of a robust Medieval imagination, but they are strange creatures in their own rights. We have ghosts as well, and people rising from the dead. Monsters and religion are, it seems, very well acquainted.

The illustrations, of course, are what bring Dell’s book to market. Many classic and, in some cases, relatively unknown creatures populate his pages. They won’t keep you awake at night, for we have grown accustomed to a scientific world where monsters have been banished forever. And yet, we turn to books like Monsters to meet a need that persists into this technological age. About to get on a plane for vacation, I know I will be groped and prodded by a government that wants to know every detail of my body. Sometimes I’ll be forced into the private screening room for more intimate encounters. And for all this I know that William Shatner was on a plane at 20,000 feet when he saw a gremlin on the wing. Like our religions, our monsters never leave us. No matter how bright technology may make our lights.

God’s Wormhole

Can God and science mix? I suppose that the third season of Through the Wormhole would be the place to look. The entire season has a distinctly metaphysical feel to it, so it is no surprise that the final episode is entitled “Did We Invent God?” It’s also no surprise that, like the other metaphysical issues explored, no resolution is really offered. Interviewing psychologists and neurologists, the show attempts to parse how scientists might address the question of God’s reality. God, of course, being immaterial, is normally understood not to be a subject discerned by science. So instead of putting God under the microscope, human perceptions of God will have to do. Everything from theory of mind to magical beliefs are probed to find hints of whence this strange idea of God might have come. The answer: we don’t know.

The more I pondered this, the more the same result reflected on science itself. When I was growing up I thought science was the truth. If science “proved” something, there was no arguing the point. I have come to realize, however, that science must be falsifiable to be science. That means it is potentially wrong. Not that it goes as far as Creationists take it to say that something is “only a theory,” but rather that science is the best explanation that we have at the moment. Future discoveries could falsify what we now know and the science textbooks would have to be rewritten. The difference here with religion is that most belief systems do not admit of this possibility. The truth has already been revealed, and there is no adding to or taking from it. God is not falsifiable. As stated above, God is not subject to science.

I don’t expect these observations of mind to change anybody’s ideas of the world. I do hope, however, that they make clear that science and metaphysics find themselves in similar situations. Both strive to know the truth. Neither can know if they’ve arrived. Both can believe it. The final episode of the season raises this point starkly. People are hardwired to believe. What they believe in is open to many possibilities, but believe they will. From my earliest days I have taken belief very seriously. What I have believed has changed over the decades, but at each step along the way I believed it was the truth at that time. I don’t know the truth. Nobody does. We all, whether scientist or religious, believe that we have found it. At the moment.

A Hollow Man

Quirky ideas stimulate the intellect. I’ve always had a fondness for the outré, those ideas slightly beyond the pale of normalcy. Sometimes taken dead seriously by intelligent people, these ideas have cultural staying power. David Standish’s Hollow Earth is a cheeky tribute to those who’ve taken the idea of the underworld to literal and literary depths. Ideas that the world might be hollow have been around for some time. Not everyone, it seems, was convinced by Copernicus and Galileo. Standish traces the more modern exemplars of those who have, with stone-faced sincerity, declared that the earth is hollow. Of course, some, such as Edgar Allan Poe, were hoaxers, but they were building on those who appear to have seriously believed it. The character after whom the mythical polar entrances to the world inside is named is John Cleves Symmes. An otherwise rational fellow, it seems, Symmes decided that the earth was like a globe and that a world much like the outside awaited those intrepid enough to get to the inside. There would be light, plants, oceans—a veritable paradise found within the earth. This strange idea survived Symmes and even the exploration of the poles could not dissuade those who believed large caverns, fed by warm, arctic oceans, awaited those who would patiently explore.

Quirky ideas stimulate the intellect. I’ve always had a fondness for the outré, those ideas slightly beyond the pale of normalcy. Sometimes taken dead seriously by intelligent people, these ideas have cultural staying power. David Standish’s Hollow Earth is a cheeky tribute to those who’ve taken the idea of the underworld to literal and literary depths. Ideas that the world might be hollow have been around for some time. Not everyone, it seems, was convinced by Copernicus and Galileo. Standish traces the more modern exemplars of those who have, with stone-faced sincerity, declared that the earth is hollow. Of course, some, such as Edgar Allan Poe, were hoaxers, but they were building on those who appear to have seriously believed it. The character after whom the mythical polar entrances to the world inside is named is John Cleves Symmes. An otherwise rational fellow, it seems, Symmes decided that the earth was like a globe and that a world much like the outside awaited those intrepid enough to get to the inside. There would be light, plants, oceans—a veritable paradise found within the earth. This strange idea survived Symmes and even the exploration of the poles could not dissuade those who believed large caverns, fed by warm, arctic oceans, awaited those who would patiently explore.

Standish notes the womb-like ideals of many of these thinkers, twisting fictional accounts together with the more deluded factual kind. In popular, and not so popular, fiction the hollow earth had a particular resonance. Jules Verne and Edgar Rice Burroughs were among its most ardent fans, using the literal underworld as a setting of strange realms. Others used the hollow planet as the location of a kind of utopia, unspoiled by humanity. Unspoiled, that is, until people arrive on the scene and do what they inevitably do to paradises. It’s in the news every day. Even Alice in Wonderland gets a nod here, as she does fall an awfully long way down that rabbit hole. Fiction writers have made a boon of this bogus idea.

The most interesting, to me, character in this story is Cyrus Reed Teed. A denizen of the Burnt Over District in New York, Teed restyled himself Koresh (yes, there were others) and made the hollow earth one of the doctrines of his new religion. Distantly related to Joseph Smith, his new faith was not as successful as that of his cousin, but nevertheless, Koresh did manage to gain a following of a few hundred and establish a compound to himself where he influenced local politics to his wishes. The story has a sad ending, however, as local ruffians (including the sheriff, like in a bad western) roughed him up so badly that as an older gentleman he died perhaps as a result of his injuries. His movement fell apart and the world grew solid once again. The world really has no place for dreamers, and yes, at such times it seems to be made of very unyielding stuff indeed.

Forbidden Words

In keeping with the spirit of freedom, just before July 4 the BBC broke the story of Iceland’s blasphemy laws having been struck down. Although the state Church of Iceland (Lutheran by denomination) supported the move, other churches have been grumbling. It’s an odd notion, that blasphemy should be illegal. Part of the oddity revolves around disagreement of what blasphemy is. Even if taking the name of God in vain is used to define it, several questions remain. Which name of God? Certainly “God” is not a name, but a title. Is taking the title of God in vain blasphemy? What does it mean to take a name in vain? If you don’t mean it? I’ve surely heard many invoking the divine in curses that were most certainly sincere. Were they blaspheming? Does blasphemy really mean failing to believe in God? And, pertinent to Iceland, which god is protected under such laws?

Religious pluralism is the clearest threat to those supporting blasphemy laws. Underlying to very proposition is the idea that there is only one true God and that is the God of Christianity. Judaism might be tacked on there, as might a reluctant Islam, but the notion of blasphemy does not seem to bother the deities of other cultures as much. Honoring and respecting belief in deities is fine and good. In fact, it is the decorous way to behave. Still, privileging one deity as the “true god” protected by state statutes is to bring politics into theology. Since when have elected officials really ever understood what hoi polloi believe? In Iceland the old Norse gods have recently come back into favor. Should they be respected to? Why not as much as the Christian God?

It is perhaps ironic that the Pirate Party put forward the successful bid to strike down the law on blasphemy. According to the BBC, the Pirate Party began in Sweden and has now established itself in 60 countries. Since it’s fight for accountability and transparency in government, it’s sure to have a hard time in the United States where bullies can run for President unashamed. What is clear is that although governments make and enforce laws, the will of the people seldom makes itself heard. We may have won some victories in recent days, but there are many entrenched ideas that benefit those in power and not their underlings. Sounds like the Pirate Party may become the Democratic Party of tomorrow. If it does, however, when it loses sight of the ideals that launched it, we may need a new party to board the ship and ask for the people to be heard. Politely, and without swearing, of course.

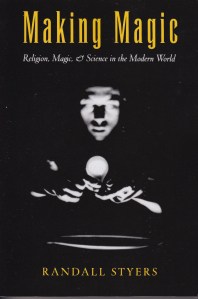

Magic Faith

We all like to believe we don’t believe in magic. In this day of sophisticated materialism, the idea that unseen forces might work upon the world seems terribly naive and not a little embarrassing. Randall Styers’s Making Magic: Religion, Magic, and Science in the Modern World has been on my reading list for a few years now. Not so much a history of magical thought, Styers offers a history of thought about thought on magic. There are several takeaways from a study like this. One is that magic and science share common ancestors. In fact, some theorists trace the origins of science to magical thought. The height of alchemy was also the period when experimental analysis of the natural world was blossoming. There was a mysterious sense to what we now think of as impassive particles whirling around for no particular reason. Making Magic makes clear that we can’t divorce developed thinking from magical outlooks. In many ways it is difficult to distinguish religion from magic.

We all like to believe we don’t believe in magic. In this day of sophisticated materialism, the idea that unseen forces might work upon the world seems terribly naive and not a little embarrassing. Randall Styers’s Making Magic: Religion, Magic, and Science in the Modern World has been on my reading list for a few years now. Not so much a history of magical thought, Styers offers a history of thought about thought on magic. There are several takeaways from a study like this. One is that magic and science share common ancestors. In fact, some theorists trace the origins of science to magical thought. The height of alchemy was also the period when experimental analysis of the natural world was blossoming. There was a mysterious sense to what we now think of as impassive particles whirling around for no particular reason. Making Magic makes clear that we can’t divorce developed thinking from magical outlooks. In many ways it is difficult to distinguish religion from magic.

Not that Styers advocates magical thought. He does, however, invite us to think about it. Another takeaway from this study is that magic, when described by religious writers, is a foil. Magic is used to show how the unenlightened think about things. Those of us here in the true light would never think such backward thoughts. Indeed, magic, as Styers makes clear, often served as a kind of social control. Lower classes think magic works wonders. The upper classes know that power lies in exploitation. Magic, in other words, can’t be divorced from politics. Those in the know would only encourage magical belief to continue. Invisible forces indeed.

Magic as a regulatory force is indeed the thesis with which Styers is working. The difference between prayer and magic is somewhat effaced when closely examined. Religious belief is seen as benefiting society while magic is for selfish benefits. I do wonder, however, where the modern magical religions, such as some branches of Wicca, would fit into this scheme. They also seek the good of society. Magic need not be selfish. Making Magic is concerned with the analysis of magic by scholars who’ve shown a surprising interest in the topic. It doesn’t really address those of today who, after finding the atomic world strangely vacuous, have turned to magic to re-enchant a world grown dull and dry. Whatever one may say about magic, it still exists, and its believers are among us. Our world with its solemn, feelingless answers could, at times, use a little such conjuring.

Peak Oil

Having no control over where we’re born, people nevertheless often feel a connection with their native region. My family had no roots in western Pennsylvania, and the consensus on why we ended up here focuses around jobs. My grandparents settled here because of a job. While working here on a job my father, from the south, met my mother. My brothers and I all consider ourselves Pennsylvanians. One of the places we liked to visit as children was Drake Well. We knew that the oil industry began in western Pennsylvania, and we knew that famous people like George Washington had traveled through the region during the various wars of the nation’s early years. The towns where I grew up are not exactly affluent, and one of them seems in danger of becoming a ghost town. Drake Well, however, the birthplace of commercial oil, still draws visitors from the region and from around the country. On a recent visit to the site, I was interested to see how religion interplayed with petroleum in Victorian Era western Pennsylvania.

Among the displays was one showing the various means used to find oil. In the days before geological surveys, finding something hidden underground required more than just technical knowledge. More precisely, it often utilized different forms of technology—some scientific, some not. Dowsing was popular, and spirits were consulted. Access to the supernatural world was not uncommon. The oil industry really took off during the same era that spiritualism began to become popular. Religion and science co-existed in a way that is difficult to imagine today. Indeed, Drake Well was established in 1859, the same year Darwin’s Origin of Species was published. The means used to reach the oil were, however, unabashedly scientific and technical. Nitroglycerin fatalities were just another fact of life.

Looking over the triumphal displays about fracking, it became clear that in the realm of petroleum production the spirit has made way for a technology with unknown consequences. The museum at Drake Well is pretty straightforward that other energy forms pose a threat to an industry that was, and currently remains, massive. We have technologies that can utilize cleaner forms of energy, but powerful oil interests have maintained the focus on more and more invasive ways to keep things going the way they are, pulling in more profits while the limited supply lasts. We know petroleum will run out. We’ve deeply integrated it into our way of life and instead of looking ahead to the next step, we’ve been reaching back to pad our fat pockets. Gone are the dowsers and spiritualists and in have charged the corporate executives. And in western Pennsylvania, the towns where the industry began struggle to stay alive as thinking that allowed for spirits has acquiesced to that which has loyalty to Mammon alone.

Useful Fantasy

Once upon a time, I heard about a book called The Uses of Enchantment. During my doctoral studies it was recommended to me, and I put it on my to read list. That list is quite long, and I don’t follow it in any kind of order. Like life, it is chaotic and ever changing. Now, some decades later, I have finally read Bruno Bettelheim’s classic, and I wish I’d read it when I first knew of it. Originally published in the 1970s, The Uses of Enchantment was one of the few serious books that suggests fairy tales are important. Bettelheim was an unapologetic Freudian and in reading his book I found the origin of many of the observations I’d read about fairy tales through the years (what does Red Riding Hood’s wolf represent?) owed their origins to this tome. The book is important even for non-Freudians because it takes great care with a subject that clearly deserves it—our imaginary tales are more than simple entertainment.

Once upon a time, I heard about a book called The Uses of Enchantment. During my doctoral studies it was recommended to me, and I put it on my to read list. That list is quite long, and I don’t follow it in any kind of order. Like life, it is chaotic and ever changing. Now, some decades later, I have finally read Bruno Bettelheim’s classic, and I wish I’d read it when I first knew of it. Originally published in the 1970s, The Uses of Enchantment was one of the few serious books that suggests fairy tales are important. Bettelheim was an unapologetic Freudian and in reading his book I found the origin of many of the observations I’d read about fairy tales through the years (what does Red Riding Hood’s wolf represent?) owed their origins to this tome. The book is important even for non-Freudians because it takes great care with a subject that clearly deserves it—our imaginary tales are more than simple entertainment.

Fairy tales are part of a long continuum in human thought. Bettelheim shows that they are very closely related to myths, although mythology is clearly something different. Similar, but not equal. Even more intriguing is the fact that fairy tales are closely tied to religion. Bettelheim notes that several biblical stories could almost be classified as fairy tales. The intellectual life of the child, he notes, for much of history depended on religious stories and fairy tales. The very unrealistic nature of both are intended to speak to children in a way that facts can’t. Indeed, the hardened rationalists sometimes seem to lose sight of the fact that we all need fantasy to keep us going from time to time. Bettelheim suggests that biblical stories help children to cope with things on a symbolic level that creates a sense of security.

Already in the 70s, however, many were suggesting that we, as a species, had outgrown our use for fairy tales. Indeed, it is not difficult to find many academics in the humanities who hear the same refrain—we don’t need this fluff. Science, numbers, technology—these are the keys to the future! But what future, I wonder? What kind of world would we have to face without literature, movies, and music? We need our myths still. Despite Disney’s take on them, we need our fairy tales as well. A world without imagination may be efficient, but it is no livable world at all. Bettelheim’s personal demons sometimes cast a shadow over his work. He was a concentration camp survivor, however, and early trauma has a way of staying with a person throughout life. Those with fairy tales to fall back onto may be those best set to survive in the deep, dark woods.

New Faiths

Scientology is never far from controversy. In the light of the new HBO documentary on Scientology by Alex Gibney (with New Jersey roots) the Star-Ledger ran a Sunday piece about the Jersey origins of the religion. L. Ron Hubbard wrote Dianetics while living in the state. The article, by Vicki Hyman, points out that the current head of the Church of Scientology, David Miscavige, grew up in the Garden State. John Travolta and Tom Cruise are also New Jersey sons. Living in a religiously diverse state has tempered my perspective on New Religious Movements somewhat. That applies to Scientology as well.

Many critics claim that Scientology began as a scam. There are those who claim that it still is. It seems clear, however, that there are many people who believe in it with all sincerity. No religion is free from episodes of abuse or poor judgment. Thus it is with human institutions. No universally accepted definition of religion exists, making categorizations difficult. What members of Scientology do, in as far as this is known, sounds very much like what other religions ask of their members. Oddness of belief is hardly unique to any religion. All ask for contributions from their members. Religions offer a community for those who belong, and many are strongly hierarchical. Even should a founder have had less than pure motives, that doesn’t translate to any less verisimilitude on the part of the faithful. Some viable religions have been based on known fictions.

Ironically, a common response to religions is anger on the part of unbelievers. (If we are believers of one religion we are, by default, unbelievers of others.) A friend of mine recently mentioned Heaven’s Gate on his blog. Although the outcome was tragic, can we say that those who followed Marshall Applewhite appear to have been true believers. Fear of Scientology may largely be based on the horrific outcomes of Heaven’s Gate, the Branch Davidians in Waco, and the People’s Temple in Jonestown. Religions can lead to people doing strange things. And those of us who live in New Jersey know that is indeed saying something.

Middle Eastern Idol

As the Passover-Easter complex of holidays approaches, our stern, scientific face turns toward the more human sensibilities of religion and its impact on our lives. PBS recently aired the Nova special The Bible’s Buried Secrets (originally aired in 2008) and when a colleague began asking me about it I figured I’d better watch it. As an erstwhile biblical scholar there wasn’t much here that was new to me, but one aspect of the program bothered me. Well, to be honest several things bothered me, but I’ll focus on one. When referring to the gods of the Canaanites, among whom the program readily admitted the Israelites should be counted, they were invariably referred to as “idols.” The problem with this terminology goes back to an issue I frequently addressed with my students—the term “idol” is a way of demeaning the gods of a different religion. Implicit in the word is the assumption of the monotheistic worldview and its attendant problems.

The Bible’s Buried Secrets seemed to adopt an overly optimistic view of the monotheistic religions sharing the same god while everyone else worshipped idols. The view is as fraught as it is simplistic. Historically Judaism, Christianity, and Islam are certainly connected. Each recognizes in the others a glimmer of its own theology and outlook, but the concept of deity has shifted somewhat at each development. Judaism and Islam are rather aniconic, especially compared to many varieties of Christianity where images are allowed, or even encouraged. It is difficult to grab the attention of the magazine-reading public with an image of invisibility on the cover. It should come as no surprise that some Jews and Muslims believe Christian images to be, well, idols.

The word “idol” is by nature pejorative. Ancient people were sophisticated polytheists. That statue that represented a deity was not thought to be that deity in any absolute sense. Rituals assured the ancients that they were instilling some aspect of divinity into the statues they used, making them sacred in the same way a Christian consecrates a church building. What’s more, it is natural for people to seek a visual focus for its devotion. It is difficult to conceptualize the Almighty as a person without giving it (often him) a body. Islam, especially, has been adamant that this can’t be done, and looking back at Christian practice it is sure to see idols abounding. As the holy days begin for our vernal celebrations, we should perhaps use the opportunity to rethink such religious vocabulary since every orthodoxy is someone else’s paganism.

Three Thoughts

If it weren’t for friends sending me little nuggets they find on the internet, I might be uninformed about much of the weird and wonderful world unfolding around me. With hours not spent at work being laid out on spartan public transit, I don’t have much time for surfing. So it was that I watched this video of St. Patrick trying to explain the Trinity to a couple of normal Irish blokes. Of course it’s funny, but as I watched it, a thought occurred to me. I used to think what a waste it was for learned minds to sit around arguing the fine points of theology. The Trinity is a prime example—three is one but not really one. Form, substance, essence, accidents or effects? What is it that makes them distinct yet not? It is, of course, a logical impossibility. Yet hearing words like modalism and arianism made me realize that these were highly sophisticated concepts. They were developed in Late Antiquity in a world with quite a different frame than our own. Atheism probably existed then, but it was very rare. What we might call naturalism did not exist. Some kind of deity or force was obvious behind the natural world.

To be sure, some thinkers had already suggested that the earth was round and that laws of mathematical precision governed aspects of nature. The frame of the human mind, at the point when engineers can construct pyramids and ziggurats, had already reached the point of science. What do you do with science when gods can’t be dismissed from the picture? Naturally, you turn your science on the gods. Although many today would argue that if God exists, the deity is a being (or concept) outside the realm of science. Science deals with the material world, not with supernatural possibilities. Dividing a single deity into three persons without making yourself a polytheist is a real mental puzzle. The concept of the Trinity isn’t biblical, although the basic ideas are derived from the Bible. It is a purely theological construction to explain how Jesus could be God and yet die. Well, it’s more complicated than that.

One of the great joys of the angry atheists is to point out the obvious frippery of theological discourse. How many angels can dance on the head of a pin? Why would anyone waste their time on such nonsense? Yet, the thinking behind early theology was exquisitely rational and highly developed. One might almost say “scientific.” The people of antiquity were not stupid. Our mental picture of the Middle Ages is often of unwashed louts chasing witches and hiding from dragons. Their society, however, was advanced by the standards of hunter-gatherers. The technology of the day may not have reached down to the level of the everyday worker, but human thought, ever restless, was working its way toward a scientific revolution. And God tagged along. Even Sir Isaac Newton gave a nod in that direction. While theological arguments may have outlived their usefulness in a society such as ours, they did represent, in their day, the best of rational thought. And in their own way, likely contributed to the birth of what we know as science.

Coming of the Green

For many years I actively attended to the calendar of saints while at Nashotah House. Although we celebrated Mardi Gras, we never seemed to celebrate St. Patrick, although he does hold a place on March 17. I suppose most people were too busy wearing black to attend to the green. I always, however, donned some verdant vestment for the day, and we usually had leprechaun gifts left behind for my daughter. After leaving Nashotah, I discovered that many universities scheduled spring break around St. Patrick’s Day. This wasn’t because of any love of the Irish or of liturgy, but because campus damage was so bad after the heavy drinking of that day, that many schools decided to let that be somebody else’s problem. St. Patrick isn’t particularly associated with alcohol, but even a quick walk by the bars of New York City demonstrates that the saint has found a home among the inebriated.

Little is known of the historical Patrick. He was associated with Lough Derg, an island of which was said to contain Purgatory. The lake also boasted a sea serpent, which may give some background to the legend associating Patrick with the banishing of snakes from Ireland. The shamrock story is likely apocryphal, but there’s no denying the brilliant green of the Emerald Isle, so the tradition developed of wearing his favorite color to commemorate the day. The traditions of Patrick grew by accretion. The Irish belief in wee folk gave legs to the leprechaun connection and, I’m told, heroic drinking might lead to the seeing of the same. One reason his day might have been downplayed liturgically is that it has become an unlikely cultural holiday. Those of us with some Irish ancestry run into some pretty high numbers.

The myth of St. Patrick is more powerful than his history. This may be a lesson for us even today. The stories we tell of our cultural heroes need not be grounded in fact in order to be meaningful. Over time the religious of many faiths have grown more and more literal to demonstrate their devotion. This is a risky proposition. We know little of the life of Patrick, or even of Jesus and other various religious founders’ lives. Their followers have been free to fill in the blanks for many centuries, building meaningful legends. I have no idea if Patrick of Ireland liked green. He may have found snakes charming. Upon an intemperate evening he may have seen leprechauns dancing about his parlor. It is less the tale that is important than it is what one might choose to learn from it.

Pauline Resurrection

Paul is dead. Has been since the first century. In biblical studies, however, he is undergoing a kind of resurrection. Studies of Paul are coming thick and fast, with many claiming, with some justification, that Christianity was his invention. Biblical scholars have long realized, however, that many New Testament letters do not come from Paul. Some never made that claim (Hebrews), while others seemed to have played on the popularity of the epistle genre and added Paul’s name to gain authority. Or maybe they were written by somebody else called Paul. Far more intriguing to me is the fact that in the authentic Pauline letters, the apostle from Tarsus mentions other letters he wrote that were not preserved. This should strike no one as unusual; would Luke’s grocery list have been preserved as scripture if it had been found? Probably not. Still, these missing letters do raise an issue that might crinkle brows with thought. What have we been missing?

Paul is dead. Has been since the first century. In biblical studies, however, he is undergoing a kind of resurrection. Studies of Paul are coming thick and fast, with many claiming, with some justification, that Christianity was his invention. Biblical scholars have long realized, however, that many New Testament letters do not come from Paul. Some never made that claim (Hebrews), while others seemed to have played on the popularity of the epistle genre and added Paul’s name to gain authority. Or maybe they were written by somebody else called Paul. Far more intriguing to me is the fact that in the authentic Pauline letters, the apostle from Tarsus mentions other letters he wrote that were not preserved. This should strike no one as unusual; would Luke’s grocery list have been preserved as scripture if it had been found? Probably not. Still, these missing letters do raise an issue that might crinkle brows with thought. What have we been missing?

Paul, like other scripture writers, had no idea he was writing “the Bible.” In fact, the Bible is one of the most obviously cobbled together holy books in world history. It is inspiration by committee. We have known for many many decades that there were other Gospels, for example. Some scholars treat the Gospel of Thomas as canonical, while others have reconstructed Q down to chapter and verse. The Hebrew Bible cites some of its sources that have gone missing. Some of the existent biblical books in their current state are obviously somewhat garbled. An imperfect scripture. And I’m wondering what Paul might have written in those missing letters.

The process of constructing a Bible has been examined time and again by scholars. Mostly they accept the material we have to work out some scheme of how Christianity decided “thus far and no further” and these books only will be Bible. Isn’t there, however, a problem when we know that other bits of parchment were floating around out there with the apostolic stamp of approval? What if Paul changed his mind over time? His current letters, the ones that survive, aren’t always consistent. It’s the job of exegetes to try to tell us what Paul really meant, but the fact is we know that this founder of Christianity sent more advice to more people and nobody bothered to keep a copy. Those bits that were preserved are not systematic or comprehensive, making me wonder just how solid a foundation a theology built on such small bits might have. Nobody, it seems, wrote a life of Jesus in real time. It took a couple decades at least before people started to sketch out his life’s story and teachings. By then Paul had already been killed. His letters, slowly gathered over time, formed a nucleus of a faith that grew to be the world’s largest. And, despite all that, we don’t know what he fully said. And we never will.

Hallowed Be Thy Income

Some time ago, I was invited to attend a “best practices” session where the language was businessese. As I suffered through statements about how everything can be quantified as numbers and how emotions should be left at the door but creativity should flourish, I began to wonder when I’d become so cynical. I mean, the presenter really believed this–it was clear from his eyes. He’d been so indoctrinated that he really believed selflessness was letting somebody else have their way when they’re your supervisor. Then it hit me. It was so obvious that I felt silly for not seeing it sooner. Corporate culture is a religion. The business world has its own specialized vocabulary, belief system, deity (Mammon), prophets, and ethics code. Those who believe it pass their teachings on to the next generation with the zeal of converts. It gives their lives meaning and purpose. It even has its own origin myth, going back to Adam Smith. All the elements are there.

A point that I come back to repeatedly on this blog is that a solid definition of religion does not exist. I once had a boss who told me there was no such thing as “religious studies.” Too many universities also believe that. When we see terror all around committed in the name of religion and our response is to decide the business curriculum is far more worth saving, I believe we’ve just decided on our religious preferences. Reward and punishment. The price of non-conformity is high. Ironically, our motivational speaker indicated that we shouldn’t be just like everyone else. Only, just don’t be too different.

I couldn’t help but to think back to an episode of Ruby Wax. While living in the UK some friends had a television license and we watched an episode or two. Ruby Wax is an ex-patriot comedian. On one episode she followed a vacuum cleaner salesman for an upscale vacuum manufacturer. Her path took her to a motivational convention which was—there’s no other way to describe this—an emotional religious ceremony. Although their god (Mammon) may not suck, his prophet (the vacuum) most surely did. At the time I saw the episode I thought it was simply entertainment, something at which to laugh. I’ve been to enough business seminars now to find that I’m a heretic in this faith. I may not know much, but I do know selflessness when I see it. And it is a trait that takes a lifetime to master and those who have belong to a different line of work altogether.

With My Luck

I wish I didn’t believe in luck. I guess I’m just not lucky that way. And I’m not alone. Of all the “superstitions” that haunt the human psyche, luck is among the most pervasive. We either have windfalls that make our lives easy, or, like many of us, a series of unfortunate events against which we constantly have to struggle. We call it luck. But is it real? William Ian Miller wrote an intriguing piece called “May You Have My Luck” for a recent Chronicle of Higher Education Review. There’s nothing as mysterious to me as the hapless professor. I mean, they have it all, right? Educated at fine schools, cushy jobs that pay reasonably well, interviews on documentaries, jobs that among the rarest on earth? Who wouldn’t want that kind of luck? (I am also a believer in myth, so that also must be taken into account.) The reason I raise luck here, however, is that Miller’s article again and again returns to religion. I don’t think it’s intentional. It’s just unavoidable. Luck, no matter how we define it, goes back in some way to the favor of the gods.

We all know people that we think of as lucky. Success seems to follow on success for them. They are at the right place just at the right moment, and their lives seem to be easy and not so full of stress as those of the rest of us. Most people, as Miller observes, have middling luck. Things go our way sometimes, and then they don’t go our way at others. My fascination, however, lies with those on the other end of the spectrum. There are those who seem to get very few breaks. They may do all the right things, follow all the wisest advice, work harder than anyone else, and still end up on the bad end of luck’s roulette. Ironically, they may be religious people to boot. Their deity, according to their sacred traditions, is the most powerful entity in the universe. And yet things don’t go their way. We call it luck. Is it more powerful than the divine?

This question, or more properly, conundrum, lies behind any concept of luck. Shifting to the paradigm with which I’m most familiar, does God direct luck or does luck exist independently of God? Does luck even exist at all? Is it just the name we give to a series of random happenings in retrospect and which have no inherent meaning? Ah, that seems to be the very point! Meaning. What do these things that happen to us mean? Whether or not we believe that life has any meaning, our minds are biologically programmed to seek it out. Very few of us are content to find only food, shelter, and air to breathe. We want something more out of life. We may not be able to name it, but whatever it is, we could conceivably call it meaning. We are looking for a purpose to our mere existence, even if we don’t believe in it. Gods or no gods, we are left trying to discern what they require of us. And whether we find it or not, it seems, is purely a matter of luck.