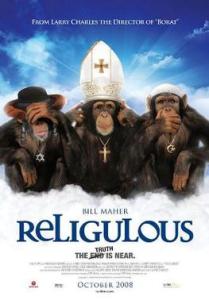

I recently rewatched Bill Maher’s Religulous. I posted on it some years ago, but time changes perspectives. Thinking back over the fun he makes against the religious, it is really only the Fundamentalist stripe that he scorns. Whether Christian, Islamic, or even Jewish, he has little tolerance for those who take their sacred texts literally. The Vatican scientist he interviews makes it through unscathed, but mainly because he’s arguing Maher’s point that the Fundamentalists aren’t at all stable. Having noted that, Maher barely scratches the patina of the whole wide spectrum of religious outlooks. Many of them are quite sensible, and some don’t even rely on the supernatural. What he seems to have overlooked is that there is a vast complexity to religious thinking and people who believe aren’t always benighted.

Long, hard reflection on religion may be rare, but traditionally the seminary was the vehicle for those with the capacity for such thinking. (Today seminaries are likely to accept just about any applicant and churches are facing shortages of clergy, making the rigorous thinking an elective course.) It’s easy to make fun of the monks in their scriptoria, but those who learned to think logically—scientifically even—about matters of belief informed the best philosophers and other ”thought leaders” of the time. If religion was the inspiration of scientific thinking (which then developed into humanism), it can’t be all bad. Certainly there are and always have been abuses of the system. Like science itself, thinking through this is a complex exercise.

Religulous is a fun movie. Bill Maher is a likable narrator and he admits, at several points, to not knowing whether there is a God or not. It is pretty easy to spot those whose religious beliefs are really more scarecrows than solid granite. Literalism is pretty indefensible in the age of smartphones and the internet. We’ve been far enough into space to know there’s no literal Heaven “up there.” But this doesn’t mean religion has no value. Many, many sensible religious people exist. Most of them don’t cause trouble for society or embarrassment for their co-religionists. Extremists, however, do both. Unswayed by the damage they do, convinced with no evidence beyond personal feeling, they are willing to risk very high stakes indeed. Those are the ones Maher is trying to take to task in his documentary. On the ground religions are complex and psychologically helpful. Complex subjects, as any thinker knows, bear deep reflection.