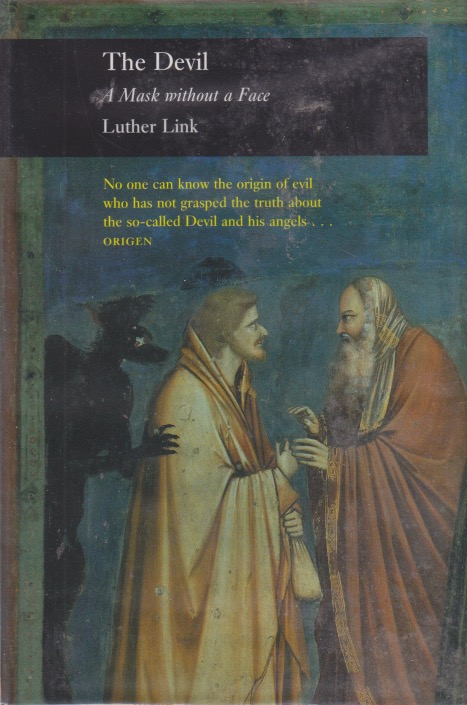

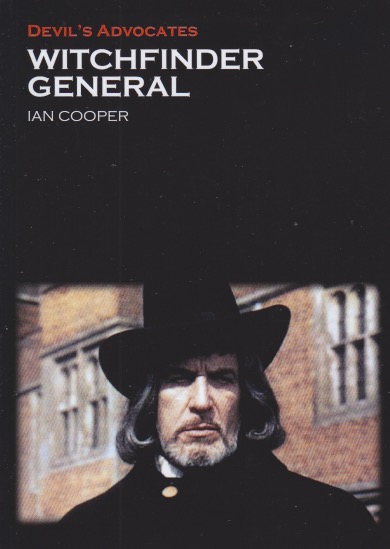

There are many books on the Devil. In fact, entire horror movies such as The Ninth Gate are based on that fact. Since writing a book on demons (Nightmares with the Bible), I read a few of the many. I’ve continued to read some further since, and one of them is Luther Link’s The Devil: A Mask without a Face. The first thing to note about this book is that it is the same as The Devil: The Archfiend in Art from the Sixth to the Sixteenth Century, as it was published simultaneously in the United States. (The former was published in the United Kingdom.) Many authors don’t realize that when you sign a publishing contract you’re selling the rights (the copyright) for your book. Some publishers or agents will sell the rights in different territories to different publishers. They don’t have to use the same title largely because, prior to Amazon it was difficult to buy UK published books in the US and vice-versa. Now a lot of “buying around” happens so books published anywhere can be purchased anywhere. (Except in authoritarian states.)

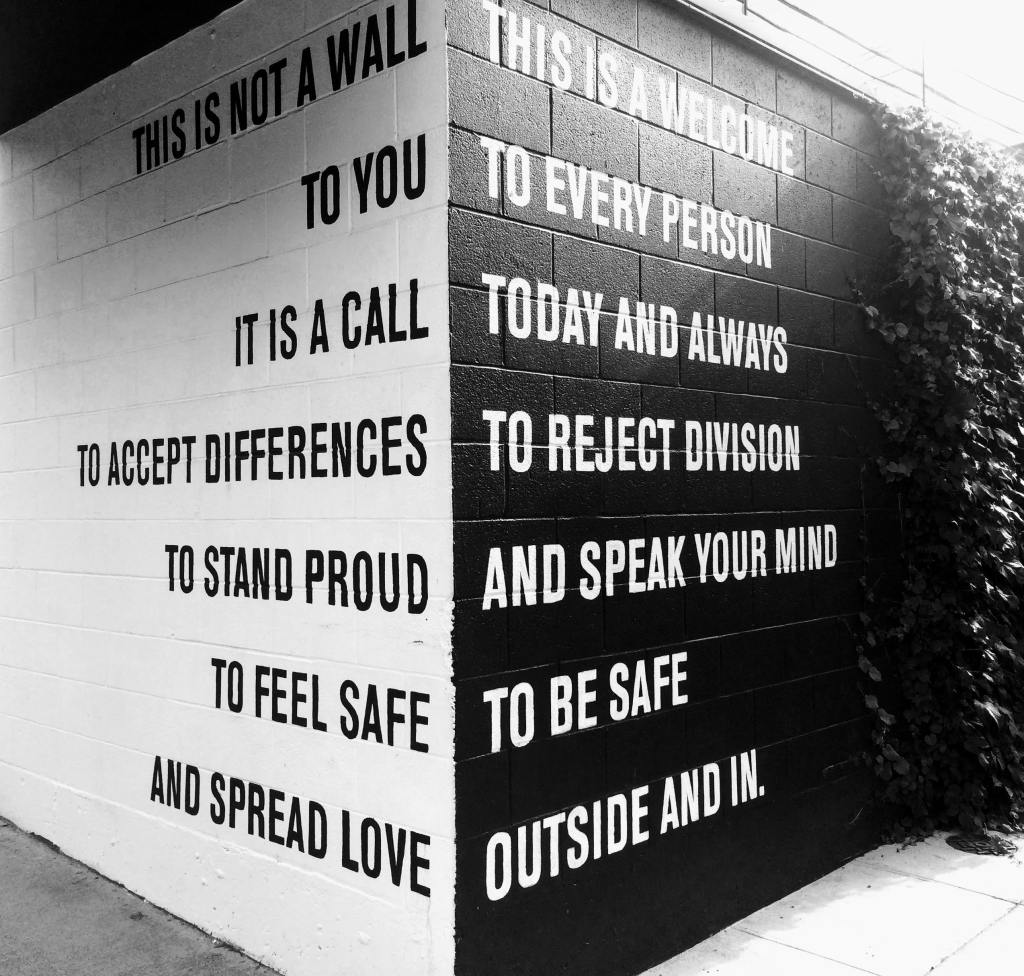

In any case, this book is a study of the Devil in art. The UK subtitle, A Mask without a Face, focuses on the conclusions drawn, whereas the US subtitle is more descriptive of the contents. There are a number of interesting points made by Link. One of the most important is that of his conclusion—the Devil, in the biblical and theological worlds of the long Middle Ages, really isn’t so much a character or “person”as a representation of “the enemy.” His looks and actions depend on the circumstances. As Link points out, to the Pope Luther was inspired by the Devil, to Luther the Pope was inspired by the Devil. Both, Link concludes, were dealing with a mask without, well, a face. Further, since the Devil does God’s bidding, whether he can be considered evil or not must be questioned.

Another interesting point is the strange continuity and lack thereof that characterize the representations of the Devil. Some of the continuities go back to an antiquity (such as ancient Mesopotamia) that had by lost by the Middle Ages. There was no real avenue of transmission since who remembered Humbaba after the tablets of Gilgamesh had been buried for centuries? This seems to point to what Jung would’ve considered archetypes. Or it could be that the same things scare people across the ages. The point of the book isn’t to be comprehensive, but it does make a good point. Anyone accusing someone of being the Devil opens themselves to the exact same charge.