When I was a post-graduate student in that Gothic city of Edinburgh, I decided to spend some time reading Umberto Eco’s Foucault’s Pendulum. It was intended as harmless entertainment, but as anyone who has read it knows, the story soon unravels into an unbelievable world of dark religions that haunt a naive protagonist. While I was reading it, a packet, hand-addressed to me, with no return address, came to my student mailbox. The contents consisted of several tracts, in German, warming of the dangers of Satanism. No letter, no explanation. Foucault’ s Pendulum had me paranoid already, and this strange package completely unnerved me. Well, I’m still here to tell the tale. While reading Victoria Nelson’s brilliant The Secret Life of Puppets, I learned that she had a strange episode while reading the same novel. It was an apt synchronicity.

When I was a post-graduate student in that Gothic city of Edinburgh, I decided to spend some time reading Umberto Eco’s Foucault’s Pendulum. It was intended as harmless entertainment, but as anyone who has read it knows, the story soon unravels into an unbelievable world of dark religions that haunt a naive protagonist. While I was reading it, a packet, hand-addressed to me, with no return address, came to my student mailbox. The contents consisted of several tracts, in German, warming of the dangers of Satanism. No letter, no explanation. Foucault’ s Pendulum had me paranoid already, and this strange package completely unnerved me. Well, I’m still here to tell the tale. While reading Victoria Nelson’s brilliant The Secret Life of Puppets, I learned that she had a strange episode while reading the same novel. It was an apt synchronicity.

Nelson is a scholar who should be more widely known. I found her because her recent Gothicka was prominently displayed in the Brown University bookstore in May. I saw it after taking a personal walking tour of H. P. Lovecraft sites. Synchronicity. I had read, in a completely unrelated selection just a couple of months ago, Jeffrey Kripal’s Authors of the Impossible. Synchronicity. For many years I have honed my Aristotelean sensibilities, following devotedly in the footsteps of science. Problem is, I have an open mind. It seems to me that to discount that which defies conventional explanation is dirty pool in the lounge of reality seekers. I have always been haunted by reality.

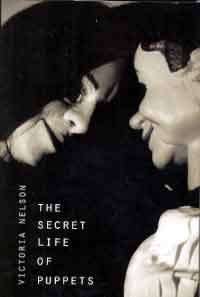

I’m not ready to give up on science. Not by a long shot. Like Nelson, however, I believe that there may be more than material in this vast universe we inhabit. Indeed, if the universe is infinite it is the ultimate unquantifiable. The Secret Life of Puppets is alive with possibility and anyone who has ever wondered how we’ve come to be such monolithic thinkers should indulge a little. For me it was a journey of discovery as aspects of my academic and personal interest, strictly compartmentalized, were brought together by an adept, literary mind. Religion and its development play key roles in the uncanny world of puppets. Those who wish to traverse the realms they inhabit would do well to take along a guide like Nelson who has spent some time getting into the puppets’ heads.