There’s this thing that you saw and you don’t know what it was called. It was, say, an architectural or engineering part of a bridge. Specifically a railroad bridge. You’ll find that even with dedicating quite a lot of time to it, the internet can’t tell you what is is called. I was recollecting something that happened to me as a child that involved a railroad bridge. I can picture the bridge quite clearly in my head, and I wanted to know what a specific feature was called. Google soon taught me that there are far too many types of bridges to get the answer to my specific question. No matter how many bridge pictures I examined, even specifically railroad bridges, I couldn’t come up with one sharing the feature I was remembering.

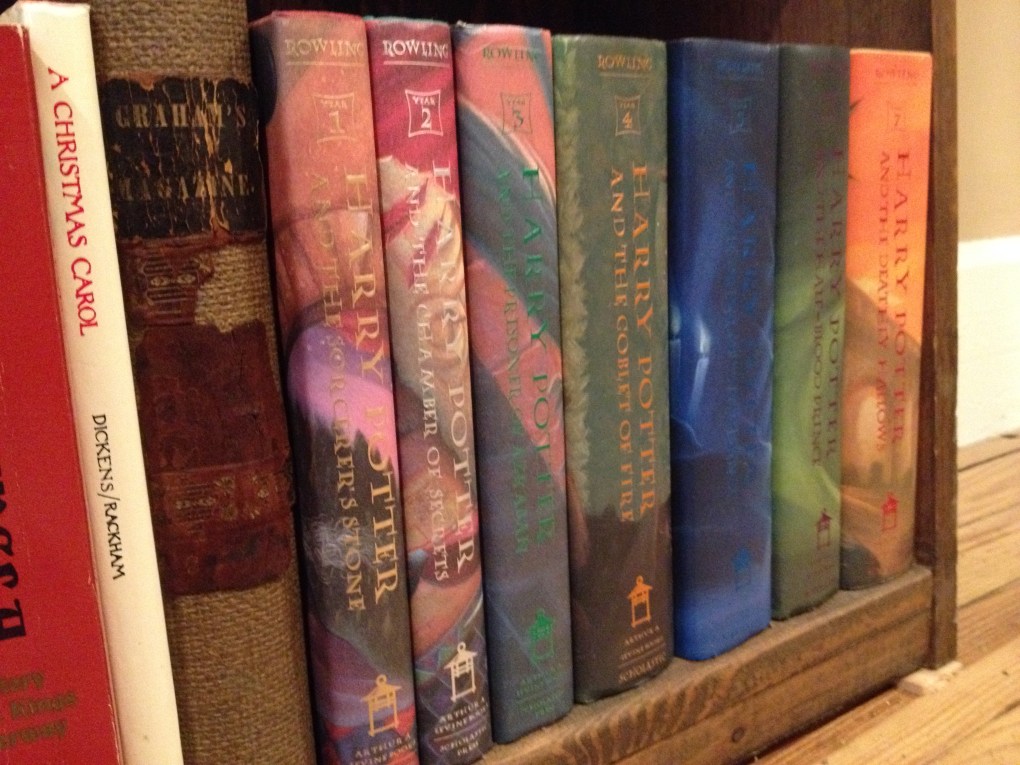

What I need is to sit down with a roomful of experts, make a drawing on the whiteboard, and see if one of them can answer the specific question: what’s this called? The web is a great place for finding information, but the larger issue of finding the name of something you don’t know is even larger than the web. Is that even possible? Yes, for the human imagination it certainly is. People tend to be visual learners. (This is one reason that book reading is, unfortunately in decline.) Videos online can convey information, and some even “footnote” by listing their sources in the description. The problem in my case is, they’re not interactive. To get a question answered, you need to ask a person. I don’t trust AI as far as I can retch. It has no experience of having been on a railroad bridge as a child when a train began to approach.

Technically, walking along railroad tracks is trespassing. Mainly this is because it’s dangerous and potentially fatal. (And somebody else owns the property.) Growing up in a small town, however, one thing guys often do is walk along the tracks. They are good places for private conversations with your friends. The added air of danger adds a bit of zest to the undertaking. Rouseville, one of my two childhood towns, was quite industrial. That meant a lot of railroad tracks. I had an experience on one of the bridges at one time and I really would like to know what the various parts are called. Just try searching for illustrations of exploded railroad bridge parts. If you do, you may find the answer to the question that I have. But the only way I’ll know that for sure is if I can point to it and ask you, “what is this called?”