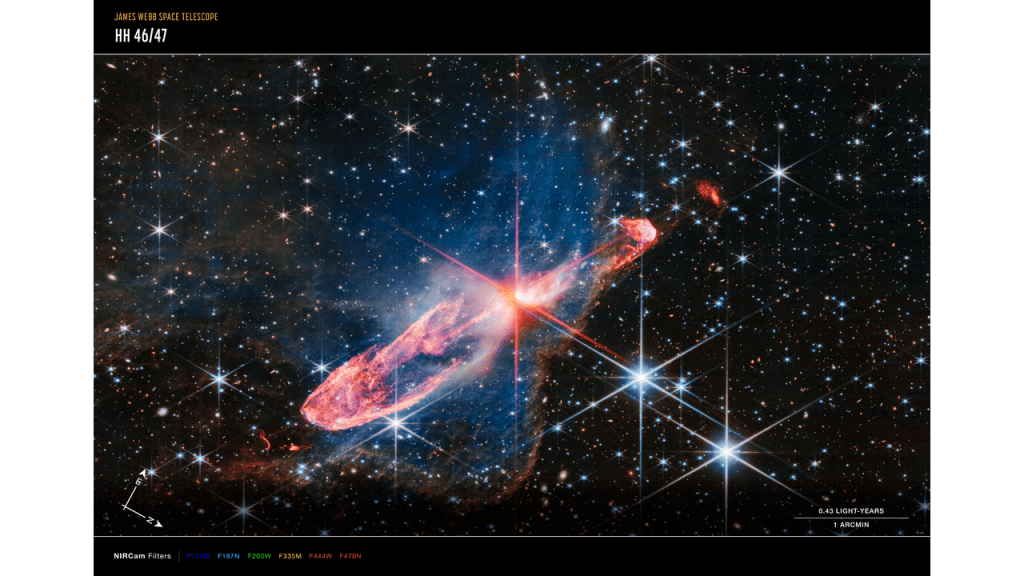

Strangely appropriate pareidolia is one of those oddly specific things that generates a lot of internet interest. I was late to find out about the “question mark” in space photographed by the James Webb Space Telescope. Okay, a couple of things: photographs, like the one below, taken by U.S. Government agencies are in the public domain (thanks, NASA!). This one can be easily enlarged on the James Webb Space Telescope webpage. To see the “question mark” you need to start from the center red star and look down to the two bright blue stars just to the left of center. The image I’m using has been enlarged so that it’s obvious. Serious news outlets have discussed this, but it’s clearly a case of pareidolia, or the human ability to attribute specific meaning, or design, to something that’s random. We see faces everywhere, but question marks are somewhat less common.

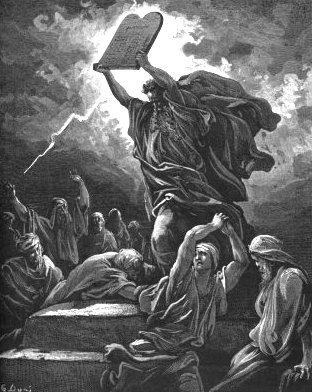

Given the state of the world—people like Trump able to continue scamming millions of willing believers for his own benefit, hurricanes hitting California, Putin going to war against the rest of the world, capitalism, war in the Holy Land—it’s no wonder that people like to think a big question mark is hanging over everything. Looking into the sky we expect to see God. Isn’t it a little disconcerting to see a huge query instead? I, for one, think it might be best if we learn to recognize false signals rather than seeing some giant message tucked away in some small corner of the universe in the hopes that we’ll turn our seeing-eye telescope that way. What font is it anyway? Does it violate some cosmic copyright?

Some signs are, I’m convinced, for real. I think they tend to be on a much smaller scale. Way down here where we can see them. What appears to be, from our viewpoint, a question mark may be seen as an exclamation point from a different angle. It’s all a matter of how we look at things. One of the most important lessons of life is that people see the same thing from different points of view. If we can accept that, others don’t seem so threatening and strange. In a small planet plagued with xenophobia, it’s important to discover strangely appropriate pareidolia every now and again to get us thinking about the deeper issues. We may not find the answers, but often asking the question is the more important thing to do.