Happy Beltane! We could use a holiday right about now. For those of us who are under the spell of intelligent horror, May Day brings The Wicker Man to mind. Not the remake, please! I first saw it about a decade ago—my career history has made watching horror an obvious coping mechanism—and I was struck by the comments that the film was a cautionary tale. One of the problems with being raised as a Fundamentalist is that you tend to take things literally and I supposed that the cautionary tale was against Celtic paganism. The Wicker Man is about the celebration of Beltane on a remote Hebridean island, and it was only as I watched it a few more times and reflected on it that I came to realize the caution was about those who took their religion too seriously, pagan or not.

Lord Summerisle, after all, admits that his religion was more or less an invention of his grandfather. More of a revival than an invention, actually. In other words, he knows where the religion came from, and he has a scientific understanding of the soil and how and why crops fail. That doesn’t prevent him from presiding over May Day celebrations to bring fertility back to the land. The people, as often is the case with religions, simply follow the leader. Of course, Beltane is a cross-quarter day welcoming spring. It is celebrated in Celtic countries with bon fires and obviously those fires are to encourage the returning of the sun after a long winter. The days are lengthening now. I can go jogging before work. The light is returning.

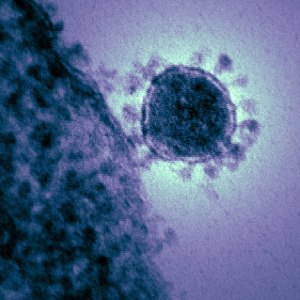

Capitalism, which is showing its weak side now, doesn’t approve of too many holidays. Like Scrooge they think days off with pay are picking the pockets of the rich. The government stimulus packages show just how deeply that is believed in this country. Celts we are not. So as I watch the wheel of the year slowly turning, and see politicians aching to remove restrictions so that money can flow along with the virus, I think that cautionary tales are not misplaced. The love of money can be a religion just as surely as the devotion to a fictional deity. Herein is the beauty of The Wicker Man. Beltane is upon us. As we broadcast our May Day it could be wise to think of the lessons we might learn, if only we’d consider classic cautionary tales.