A friend recently asked me to write a post on the feminine image of God. Specifically, she noted that images of God tend to be overwhelmingly male, even today. Having written a book on the goddess Asherah, and being very interested in gender equality issues, I was intrigued by this request. Growing up male it seems natural in our culture to find representations of God as a man. It stands to reason that in a culture more open to feminine experience we should find female images of God. They are, however, still lacking. This combination of improbable facts kick-started some ideas about both religion and culture. To begin at the beginning, although the Bible makes passing references to God as either non-gendered or even female in rare places, clearly the predominant metaphor is masculine. The third-person masculine singular pronoun (i.e., “he”) is almost always used for God, beginning in Genesis 1 and running straight through. The Judeo-Christiani-Muslim deity is decidedly male in his demeanor. All three religions developed in circumstances of male social dominance.

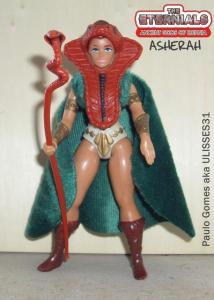

Enter the 60’s (1960’s, that is. C.E.). Women were able to begin expressing their needs without the whole weight of a social McCarthyism bringing down the girth of the government upon them. Instead of finding feminine traits to the god of the Bible, interest in goddess worship revived. Now, serious scholars disagree on just how much a role the goddess played in the development of monotheistic religions. The end result, no matter how you parse it, is pretty masculine. Therefore some women found the goddess to be more conducive to fulfilling their needs. Problem is, there never was, historically, a goddess monotheism. There were always goddesses, plural. Without the unifying force of a single, female deity societies just never fully coalesced around a single, strong image of feminine deity. Some have tried to put Asherah in that role, but she was defined by her husband El and shared the stage with Anat, Shapshu, Ashtart, and a host of other potent females. In a world of two basic genders, monotheism favored the male.

Are there female images of god? Undoubtedly there are. There will be a great deal of difficulty finding them because Christianity very quickly invented the idea of heresy (something Judaism fortunately lacked). This assured that the “orthodox” voice would always be the loudest in the shouting match that we call religion. This situation has had two millennia to ferment and brew. Theologians (mostly male) early on stated that God really has no gender. After all, a male god does imply a lady somewhere in the wings—otherwise human maleness is really superfluous, theologically speaking. Rather than embrace castration, let’s just keep god male, the thinking seems to go. Religions are conservative by nature. They may breed radical free thinkers, but natural selection comes to their rescue by reinforcing the bearded, chastely clothed, divine father. Until society is ready to embrace true equality, however, religion will continue to privilege the big man upstairs.