I finally had to break down and buy it. Quatermass and the Pit has been on my “to see” list probably longer than any other single movie. I managed to stream the first two of this telinema series for free, so I guess it was like getting three movies for the price of one. Aired in the United States as Five Million Years to Earth, this isn’t the greatest sci-fi-horror movie ever, but it isn’t bad. The pacing is a bit slow but the story is intriguing. Rocket scientist Quatermass gets involved in the excavation of what turns out to be a buried rocket ship from Mars. Surrounding the ship in the five-million-year-old matrix are the remains of apparently intelligent apes. The scientists discover that the apes were artificially enhanced by insectoid martians that resemble the devil. It’s pointed out that any time digging has taken place near Hobb’s End, strange phenomena occur. It’s noted that Hob used to be a nickname for the devil.

This detail leads to a perhaps unexpected connection to religion and horror. Quatermass and Barbara, a scientist who has the ability to “see” the creatures via collective memory, realize that the hauntings that have taken place around Hobb’s End for centuries may have been the image of demons, or the devil, emanating from the evil of these would-be invaders. At one point a priest argues that their influence is essentially demonic, but the scientists realize that these modified apes are actually the creatures from which humans evolved. All the human tampering with the ship eventually frees the spirit of the martian insects, resembling a devil. The way to destroy it is with iron, relying on folklore which, in this instance, works.

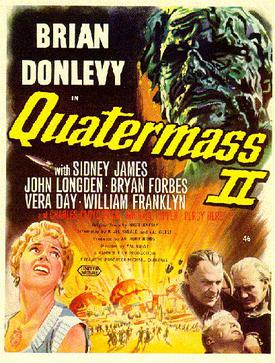

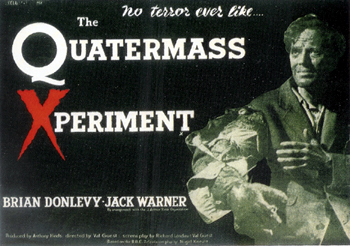

The four Quatermass movies (I don’t plan on seeking out the last) were theatrical reshoots of television serials. The last movie is essentially the TV series stitched together as a movie. From at least the seventies on (Quatermass and the Pit was released in 1967) the first and third installments were considered fairly good horror films. They aren’t always available in the United States, probably due to digital rights management. It seems ridiculous that in this day and age that companies still restrict access, even to those willing to pay a modest fee, for movies that are essential parts of the canon. Hammer (all three Quatermass movies are Hammer productions) films are still difficult to access in the United States. At least, with the willingness to wait half a century, I’ve finally be able to see Quatermass and the Pit.