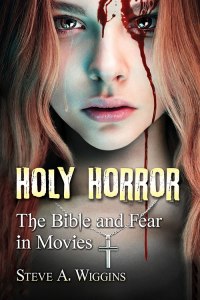

So how much time is there? I mean all together. I suppose there’s no way to know that because we have no idea what came before the Big Bang. Those who invent technology, however, seem not to have received the memo. New tech requires more time and most of us don’t have enough seconds as it is. Perhaps in the height of folly (for if you read me you know I admit to that possibility) I’ve begun uploading material to my YouTube channel (I hope I got that link right!). These are cut-rate productions; when you’re a single-person operation you can’t fire the help. I figured if those who don’t like reading prefer watching perhaps I could generate a little interest in Holy Horror visually. (I like my other books too, but I know they’re not likely to sell.)

The question, as always, is where to find the time for this. My nights are generally less than eight hours, but work is generally more. What else is necessary in life, since there are still, averaged out, eight more left? Writing has its reserved slot daily. And reading. Then there are the things you must do: pay taxes, get physical exercise, perhaps prepare a meal or two. Soon, mow the lawn. It may be foolishness to enter into yet another form of social media when I can’t keep up with those I already have. What you have to do to drive interest in books these days! I think of it as taking one for the tribe. Readers trying to get the attention of watchers.

There’s an old academic trick I tried a time or two: double-dipping. It works like this: you write an article, and another one, and another one. Then you make them into a book. I did pre-publish one chapter of a book once, but getting permission to republish convinced me that all my work should be original. That applies to reviews on Goodreads—they’re never the same as my reviews on this blog—as well as to my YouTube videos. There’ll be some overlap, sure. But the content is new each time around. So you can see why I’m wondering about time. Who has some to spare? Brother, can you spare some time? I’ve been shooting footage (which really involves only electrons instead of actual linear imperial measures) for some time now. I’ve got three pieces posted and more are planned to follow. If only I can find the time.