The idea is a simple one. When someone undermines, the very foundation of an idea is left with no foundation. We are taught not to undermine ourselves; for enemies it’s okay. Encouraged even. The Bible contains the seeds to its own undermining. The claim that it is a sacred book encourages—even demands—serious attention be paid to it. When it is examined closely, however, it becomes plain that the status accorded it as a book undermines its own claims. Believers can respond in several ways. One is to declare the Bible inerrant and to claim that contradictions are not contradictions and that what history has proven false is actually true. The keenest breed of such inerrantists hardly exists any more, since it does require a stable, geocentric view of the universe, if a universe there be at all. On the other extreme there are believers who make sacred writ so highly symbolic that we need not worry about the obvious factual errors—they were never meant literally anyway. And, of course, every position in between.

The idea is a simple one. When someone undermines, the very foundation of an idea is left with no foundation. We are taught not to undermine ourselves; for enemies it’s okay. Encouraged even. The Bible contains the seeds to its own undermining. The claim that it is a sacred book encourages—even demands—serious attention be paid to it. When it is examined closely, however, it becomes plain that the status accorded it as a book undermines its own claims. Believers can respond in several ways. One is to declare the Bible inerrant and to claim that contradictions are not contradictions and that what history has proven false is actually true. The keenest breed of such inerrantists hardly exists any more, since it does require a stable, geocentric view of the universe, if a universe there be at all. On the other extreme there are believers who make sacred writ so highly symbolic that we need not worry about the obvious factual errors—they were never meant literally anyway. And, of course, every position in between.

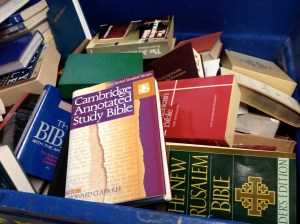

The Bible is not a unified composition. This was evident to the person, whoever it was, who first joined the Prophets to the Torah. Or even Genesis to Exodus. We have no way of knowing if s/he (mostly likely the latter) really believed that Moses wrote all the stories from the creation of the world through his own death, but the books of the Pentateuch roughly hang together in an extended narrative with plenty of instruction along the way. The “Bible” that Jesus knew had considerably fewer books than our “Old Testament.” And one gets the sense that Paul’s letters were tacked on in a catch-as-catch-can fashion, with everyone knowing (as the letters themselves say) that material is missing. And what Paul authoritatively wrote to the people of Galatia may not have been the same advice he sent to the Corinthians. Tides and times. Bibles and believers.

When scholars began, out of deep devotion, to look closely at the Bible the cracks in this historical facade began to fracture. Once the breach is in the dike, one dare ignore it only at great peril. The first shaft had been dug. By the time of Julius Wellhausen, the undermining was already engineered and well underway. And it couldn’t be stopped. Biblical scholars had choices to make: ignore the evidence and continue to sing the Lord’s song in a strange land, or climb out of that tunnel before it caves in. And the church, unsuspecting of what it means, insisted on an educated clergy. Serious study of the Bible shows what many believers wish it didn’t. And yet we continue to make claims based on evidence that is faulty. Just as long as these supporting pillars hold up we have nothing to worry about. And the undermining continues daily, lest we all find ourselves in the breadline.