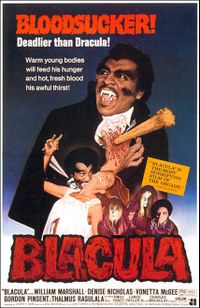

The first of the “blaxploitation” movies, Blacula is a period piece. In 1972 vampires were still all the rage, following from Dark Shadows and the continuing Hammer hammering of the monster. They even produced Dracula AD 1972, not to put too fine a point on it. American International Pictures wanted in on the action and produced the first Black vampire in cinematic history. Rather than a remake of Bram Stoker’s novel with a Black cast, the story begins with Mamuwalde, an African prince, entreating Dracula (whom he doesn’t know is a vampire) for help ending slavery. Instead, Dracula turns Mamuwalde into a vampire that he names “Blacula,” and places him under a curse. In the seventies, a homosexual couple purchases Dracula’s castle, intending to sell the contents on the antique market. One of those antiques is a locked coffin.

Once he’s freed in America, Blacula quickly runs into Tina Williams, the spitting image of his long-deceased wife. Meanwhile Tina’s friend Dr. Gordon Thomas, suspects that there is a vampire on the loose in LA. Although the opportunity for camp is clearly present, this movie is played straight. Mamuwalde is a monster—he kills several people—but his real motivation is to regain his dead wife, whom, he is convinced, is Tina. When Tina is shot by a trigger-happy cop in the tunnels below a chemical plant, Blacula turns her into a vampire. When she is staked, Mamuwalde tells the doctor that he need no longer pursue him. He voluntarily climbs into the sunlight and dies.

Now, this wasn’t a great movie but it does seem to have a reasonable bit of social commentary. It was the seventies, but racial and orientation slurs were still widely accepted. And people dressed like, well, it was the seventies. The Black characters, however, are portrayed with dignity, and Mamuwalde is presented as nobility. Perhaps more importantly, this movie opened the doors for further horror films featuring African-American lead characters and plots. A few decades later Blade, based on a comic book hero, would once again foreground a Black vampire who’s on the side of good. It’s still some distance from Black Panther, but the process had to begin somewhere. Watching Blacula was like watching history, and I suppose viewing movies is like a selective piece of history. By this point AIP was well established, and influential in its own way. I’d heard about Blacula since childhood, but until streaming it never really came across my screen. Nevertheless it remains an important piece in this country’s ongoing vampire mania.