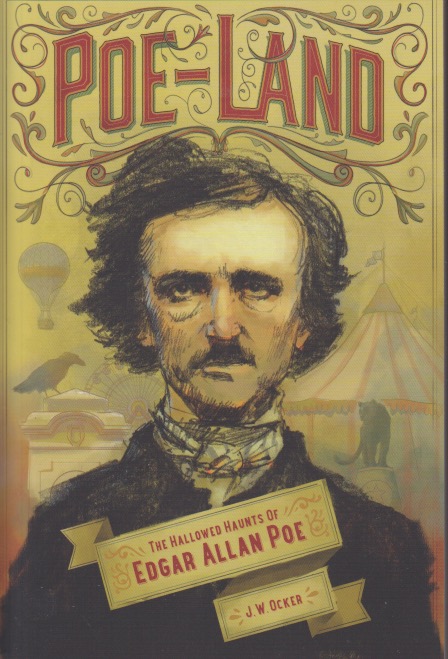

J. W. Ocker’s Poe-Land is a book I read too late. That’s not to denigrate its status as the best book I’ve read this year—no, not at all. It’s just that, unaware of Ocker’s book, I’d visited many of the Poe sites in America without the advantage of the full story. Since my daughter also appreciates Poe, we’d gone to the Poe house in Philadelphia and the Free Library where Dickens’ stuff raven lives (sort of). We’d gone to see Poe’s grave in Baltimore and his reputed dorm room at the University of Virginia while she was on college campus tours. We attended the Poe exhibit at the Morgan Library in Manhattan. We’d even gone to Fort Moultrie in South Carolina, stopping at the Poe Tavern on a family reunion trip to Charleston. On my own, I’d sought out Poe’s birthplace on a business trip to Boston. (The plaque was not there when I lived in the city.). Poe-Land is Ocker’s travel log of an intentional visit to all of these places. (I should mention that we also went to Richmond to see the southern family but I arrived with a migraine and we had to put off the tourist stuff for another trip. And I was distracted by Lovecraft on my two trips to Providence.)

To a Poe fan, and I can count myself as no other, this book is itself a treasure trove. Ocker took a year to visit the Poe sites, north to south and even to England. He writes about what he found and the people he met. These people are likely my tribe, but I tend to work alone and know people primarily virtually. I’ve tried to get museum people to let me behind locked doors, but I don’t have the clout. (When I was a professor I had a bit more pull.) I enjoyed every page of Poe-Land. It was a book I didn’t want to rush through since it made me smile knowing that for reading time the next day I’d still have more to go. And I learned a ton about Poe.

I’ve read several books about Poe, of course. As an ignorant kid, I bought a used copy, in five volumes, of his collected works and biography. I bought it at Goodwill and treasured it. Until as an ignorant (and poor) college student, I resold it along with many of my childhood reading treasures. I read biographies in the school library. And I’ve read (and bought for good) some as an adult. I even mention Poe in most of my books, including Sleepy Hollow as American Myth, because he’s part of my story too. Poe-Land was easily my favorite book of 2025. Now I want to read more about Poe. But in the end I face a dilemma. Do I read more about Poe, or do I go back for another of J. W. Ocker’s books?