It’s probably safe to say that most Americans my age were influenced by television when they were young. Since I’m a late boomer, I fit into the “monster boomer” category and I suspect that if you gathered us all in a room you’d discover we had some of the same watching habits. I confess to having watched a lot of TV. I will also admit that some of it was absorbed particularly deeply. I mean, I liked shows like Scooby-Doo, Jonny Quest, Get Smart, Gilligan’s Island, and even The Brady Bunch. While I still quote from a couple of these from time to time, they never penetrated as deeply as a number of other early fascinations. I saw nowhere near every episode of The Twilight Zone, but those I did see absolutely riveted me. They still do. As an adult I’ve read many books on or by Rod Serling. There’s depth there.

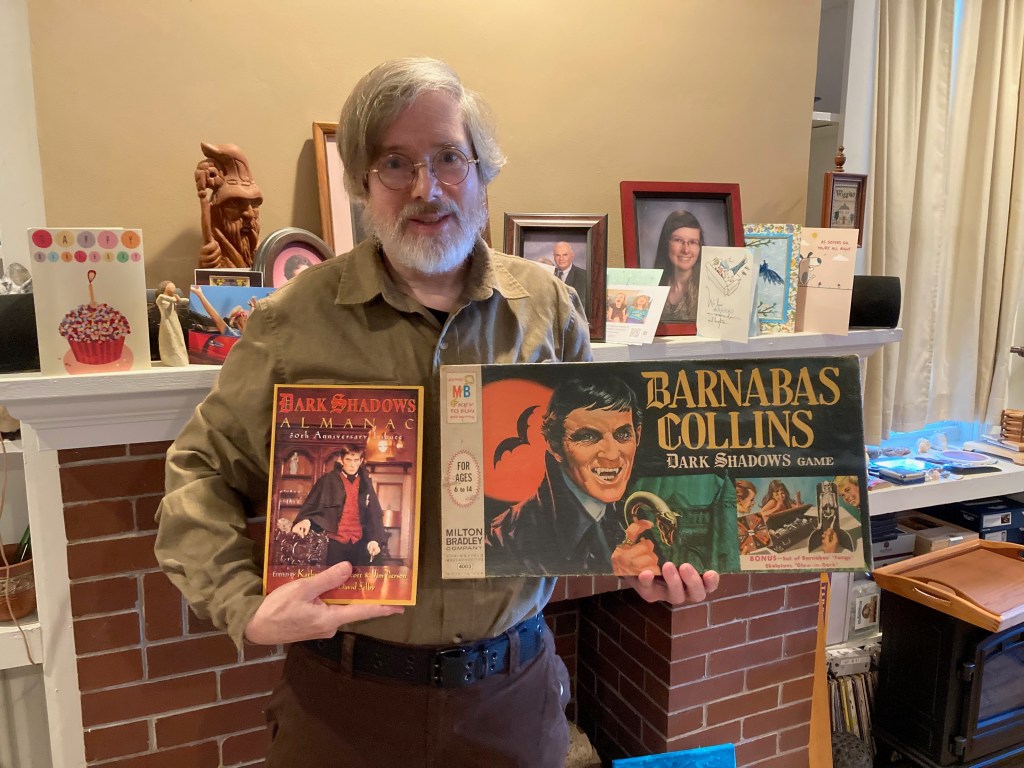

Another strong contender for real influence is Dark Shadows. Again, I never saw all the episodes but it created in me a feeling that no other television show did. My breath still hitches, sometimes, when I think of it. I watched the show and I bought used copies of the novels by Marilyn Ross. As an adult I even collected and read the entire lot of them. And I’ve read a book or two about Dark Shadows. And one about Dan Curtis, the creator of the series. Recently a good friend, aware of this particular predilection, sent me the Barnabas Collins game and a copy of The Dark Shadows Almanac. I have to admit that it was difficult to work the rest of that day!

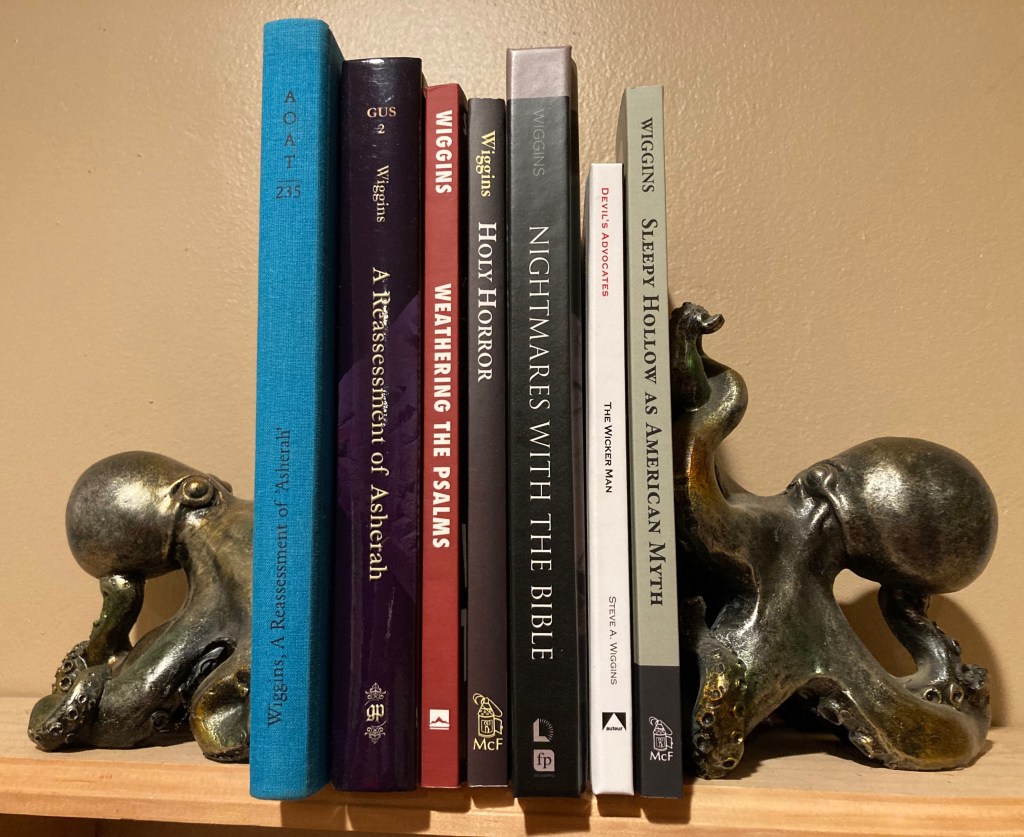

Probably the last very influential television show—more from my tween Muppet Show era—was In Search of… This I watched religiously, and, like Dark Shadows, I went out and bought the tie-in books by Alan Landsburg. One thing all three of these series (Twilight Zone, Dark Shadows, and In Search of…) have in common in my life is that I purchased the accompanying books. Those that I foolishly got rid of when I was younger I have reacquired as an adult. Sure, there’s some nostalgia there, but these shows were more than mere entertainment. They have helped make me who I am today (whoever that is). I rediscovered my monster boomerhood after losing my tenuous foothold in academia and saw that other religion scholars were writing books about these somewhat dark, and deep, topics. So I find myself with friends ready to help indulge a fantasy and a shelf full of books that many my age would be embarrassed to admit having read. But chances are they too were influenced by television, even if they hide it better.