Many years ago some friends took us to the Mercer Museum in Doylestown, Pennsylvania. Bucks County is one of those places where oddities persist, and I was very impressed by the fact that the museum had an actual vampire-hunting kit. Now this was before the days of sophisticated cell-phone cameras and my snapshot, through glass, wasn’t very good. There was no way to know, at the time, that a few years later Vampa: Vampire and Paranormal Museum would open up just a few miles down the road. And that the latter would have a whole room full of actual vampire-hunting equipment (advertised as “Largest collection of vampire killing items ever in one location”). A very real fear of vampires existed in Europe up until the technologies of the last century showed that humans don’t need the undead to create fear. In any case, many chests of vampire-banishing implements line the first room.

And stakes. As my wife noted, in the movies they just grab a stake and mallet and get to work. These were stakes made by craftsmen. Many of them intricately carved, and, one suspects, officially blessed. Matching sets of stakes and mallets seem like they were for display, rather like some firearm collectors these days proudly show off their guns. The odd thing, to my mind, is that most of these artifacts weren’t medieval, but from the early modern period. The earliest I saw was from the seventeenth century. I had to remind myself that Europe was undergoing a very real vampire scare the decades before Bram Stoker wrote Dracula. John Polidori, Lord Byron’s associate, had written a vampire novel in the early nineteenth century, well before Stoker’s 1897 classic.

Vampire maces were of a higher magnitude. The spiked mace, with crucifix, shown here, is an impressive piece of woodworking, as well as enough to make any vampire think twice before biting any necks in this house. The idea of the Prince of Peace adorning such an instrument of violence encapsulates the contradiction of being human. And the depths of our fears. This museum is a testimony of our collective phobias. Few people in this electronic age really believe in physical, supernatural, vampires. There are people who do, of course, but most of us are so entranced by our phones as to completely miss a bat flitting through the room, let alone a full-fledged undead monster with fangs. The fact is, over the centuries many people did gather what was needed to protect themselves from vampires in chests and cabinets, all in the name of fear.

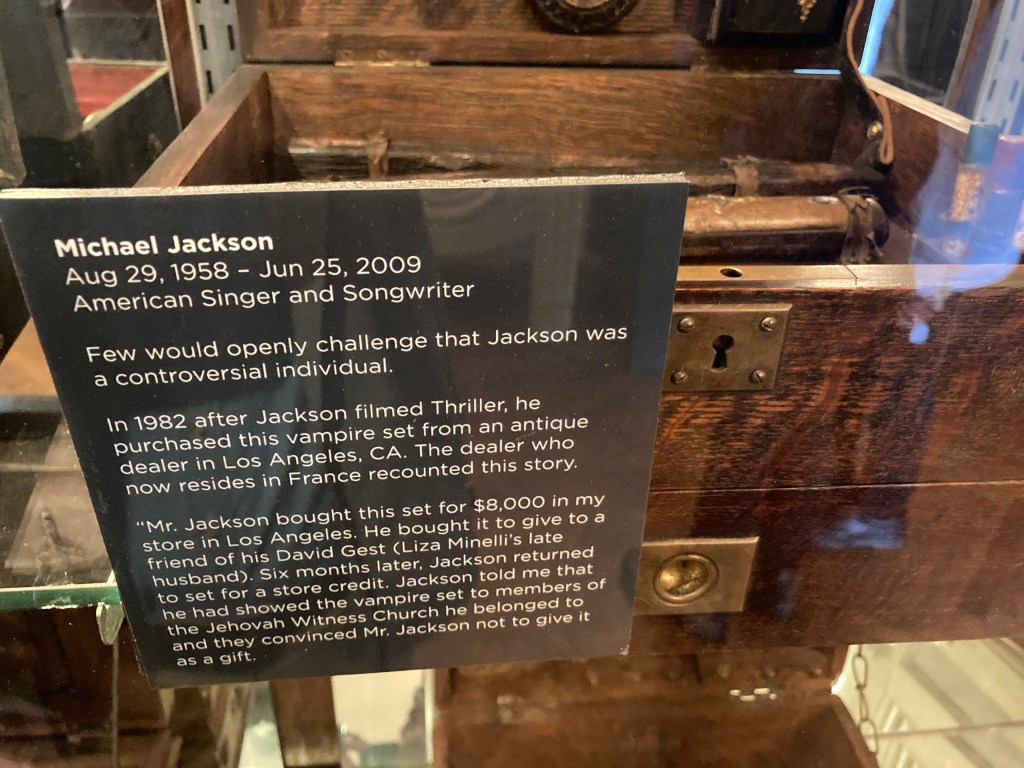

One final note: one of the vampire hunting kits was owned by Michael Jackson. As the sign (with a typo) notes, the Jehovah’s Witnesses (to which both he and Prince belonged) convinced him not to give it as a gift. Belief, it seems, persists even into the late twentieth century.