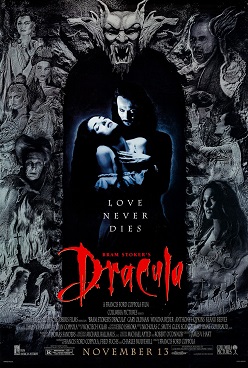

Francis Ford Coppola’s Bram Stoker’s Dracula is one of the “old movies” about which I posted some time back. I’ve seen it at least a couple of times, and I wrote a previous blog post about it (October 11 2009). This is a film about which I have conflicted feelings. It has immense visual appeal and it influenced a tremendous number of followers. It also did exceptionally well at the box office. Since 1992 was a year in which I’m pretty sure I saw no movies in the theater (finishing a doctorate, moving back to America, and commuting weekly from Champaign-Urbana to Nashotah House drained my time and energy. Besides, still being fairly newly married, I had not transitioned to horror movies again (that’s a different story, also involving Nashotah).) Being a former literalist, when I first saw it I resisted the title since it takes significant liberties with Stoker, but the overall story is probably the closest of any vampire movie I’ve seen.

The strengths of the movie include its interaction with religion. Vlad begins by renouncing God and becoming an agent of evil, stabbing a cross, and drinking the literal blood that pours out. A number of Stoker’s own religious elements are also portrayed, and the ending brings God back into the picture, implying a kind of redemption for the defeated vampire. The stylishness and opulence of the movie also make for engaging viewing. It doesn’t have the gothic feel that it might—there seem to be some almost Burtonesque elements to it and some of the casting decisions feel ill fitting. Anthony Hopkins just doesn’t do it for me as Van Helsing. His one-liners feel out of place, and his interpretation of Van Helsing as a whole doesn’t resonate with me.

I do like Gary Oldman’s Dracula, however. He’s right up there with Lugosi (but not quite at that level). The conflicted vampire is an appealing character—much more intriguing than the pure evil kind. This Dracula forsakes God because church rules about suicide keep his Elisabeta out of Heaven. Even now the rulings seem not to allow for much nuance. At heart, the vampire is a religious monster. Fear of the crucifix may go back to Bram Stoker, but this movie tries to give it a backstory. It’s a question of theodicy—why bad things happen to good people, essentially. This is probably the biggest reason people end up turning away from religion, and it’s something theologians ponder. While it isn’t my favorite vampire movie, Bram Stoker’s Dracula is stylish and accurate to a degree. But it also turns back the pages a bit further than Stoker’s book does.