While trawling the internet over the weekend, I came upon an interesting article that ties together religion and paranormal belief. According to ADG, a unnamed woman (already the question marks erupt) in Galilee in 1967 was visited by aliens. Instead of photographing them, as most unnamed women would, she followed their instructions to point her camera at the lake (Sea of Galilee) and snap one for the album. When she turned back around the aliens were gone, and when she had the film developed there was a picture of Jesus and a disciple or two, walking along the sea in earnest conversation. Well, one doesn’t have to be a scholar of Tobit to spot the apocryphal, and this obviously bogus story received far more hits than any of my posts do. People are fascinated by the concept, even though most of the comments show some healthy skepticism.

To me the fascinating aspect is that religion and paranormal topics hold hands so easily. That is not to suggest they are the same thing, but rather that they are both perhaps directed toward a similar goal. We find ourselves in a cold world, often. There are cruelties, atrocities, and a disheartening lack of care for others. We want to believe that somebody out there has got our backs. Is it so different to believe that God dwells in the sky than to believe that aliens do as well? What is more important than the putative fact of such celestial dwellers is the belief in them. Our minds, no matter how we may protest otherwise, are perfectly well aware of their own limitations. We can’t know everything, and so we must believe.

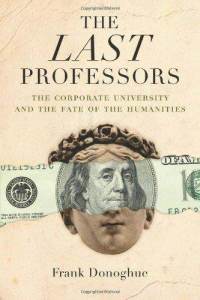

Many of us find ourselves in an uninspiring cycle of work, sleep, and work. Sometimes we actually even do sleep, too. Cogs in a capitalistic money machine, we leave our weekends free (sometimes) to pursue a little meaning. As much as some may castigate religion, we should not forget that without it we would not have the weekend! For a little while we can break the meaningless cycle, the treadmill upon which we heavily thump our way through five days out of every seven. Is it any wonder that so many want to believe that, like Calgon, aliens might come to take us away from our drudgery? If that doesn’t work, there’s always religious services. All you have to do is point your camera and believe.