Some time back I posted about Steffanie Holmes’ Pretty Girls Make Graves. It was a first book in a duology and since I’d been trying to keep up with dark academia, it was a recommended exemplar. As I mentioned in that post, the book ends with a cliffhanger, so I got to Brutal Boys Cry Blood as quickly as I could. Holmes is a prolific self-publishing author and I found Pretty Girls much better written than the majority of self-published material I’ve read. Brutal Boys picks up right where the previous novel left off, freeing George Fisher from her predicament and moving her into new ones. At Blackfriars University, George is investigating the death of her former roommate. The Orpheus Society, consisting of old money blue bloods, seems to be involved in more than wanton destruction of property and orgies.

Much of the first half of Brutal Boys sets the scene for a relatively happy period in George’s life. She establishes a polyamorous relationship with the uberwealthy student William Windsor-Forsyth and Father Sebastian Pearce, a teacher and college chaplain. The three of them are mutually in love, but even as George is admitted the Orpheus Society, a deeper part of the sect emerges. This group is even more insidious and has designs on human sacrifice. But I’ve already said too much.

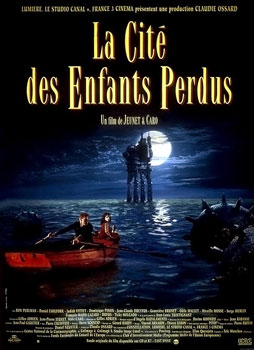

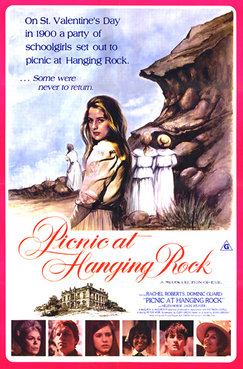

Reading is, of course, a subjective exercise. My personal experience of this duology is that the first book is better than the second. It’s not that I feel Brutal Boys is a bad story—it keeps your interest pretty much the whole way through—it just seems to be far more improbable than the first novel. It is fiction, of course, and there is nothing speculative here. There are no ghosts or monsters or divine intervention. Speaking strictly for me, it might’ve helped with believability if there were a little of this. I was not one of those swept away by Donna Tartt’s inaugural dark academia novel The Secret History, but she did include just a little of a speculative element that allows for a reader to perhaps convince him or herself that this might just possibly happen. Some writers and readers prefer not to use that escape hatch. I’ve read good dark academia both with and without speculative aspects to the story, but to me, such mystery adds a little depth to what might be happening. And I admire self-publishing authors who write well enough to draw you into a second book, which can be a rare thing.