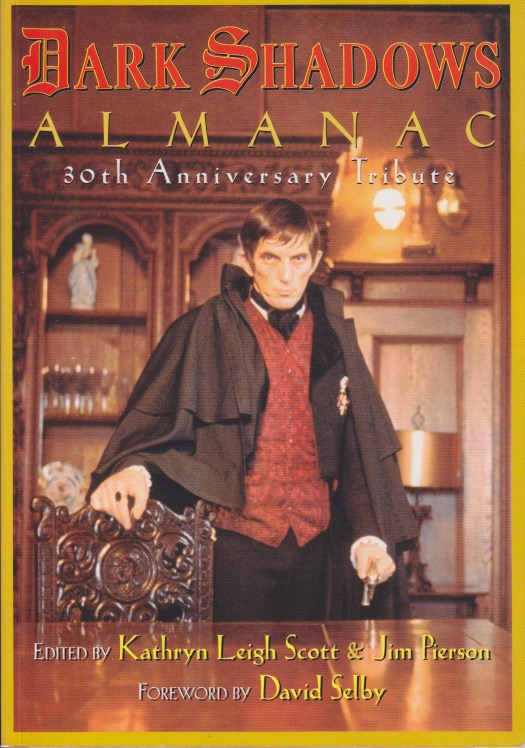

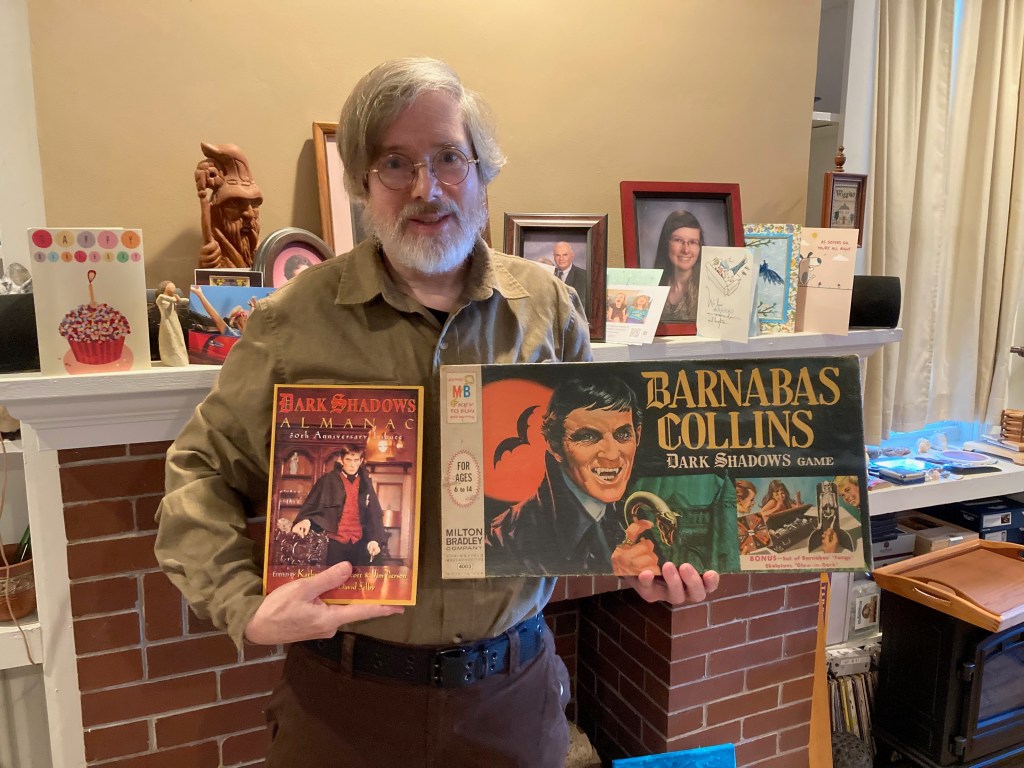

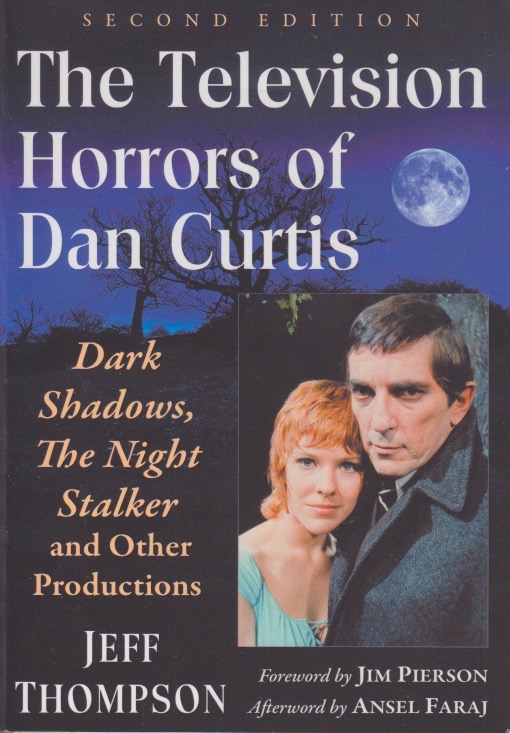

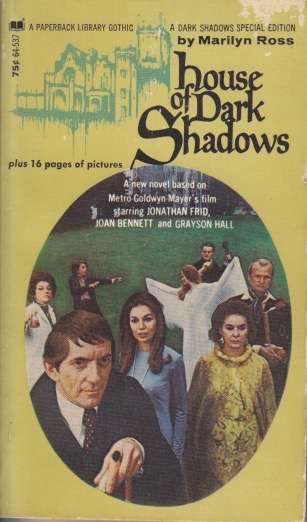

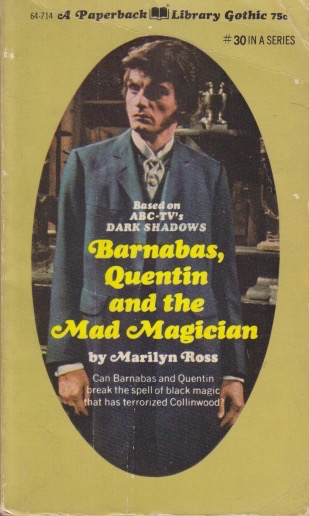

Since noting some months ago that I’d discovered Dark Shadows on Amazon Prime, it’s no surprise that I’m squeezing in an episode here and there, where I can. Amazon begins “Season 1, Episode 1” at the point Barnabas Collins appears. This was actually ten months into the daily, but it saves a few hundred dollars buying the DVDs. I honestly remember little more than impressions of the soap opera from childhood. I can’t say which episodes I saw during the initial run, but I do know that they were formative in my appreciation of horror. It turns out that many famous people in various media were childhood fans of the show. It certainly wasn’t the slickest production but it manages a mood that’s difficult to match. It’s what Edgar Allan Poe called “effect,”—he felt that a short story should maintain a single effect, something that he did most notably in his macabre tales.

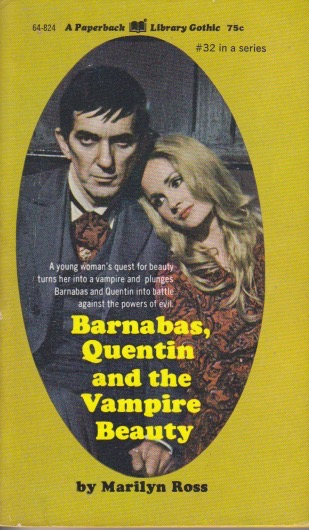

I recently watched, in Amazon’s numbering (and I realize Amazon didn’t come up with this, it was a rebroadcast release that someone decided should start when the show became popular) episode 22 in season one. This particular episode surprised me in that it actually had a legitimately scary ending. Now, soap operas are very slow unfolding of stories, as most television watchers know. Things don’t change quickly and action-packed content requires a lot of time to set up and film, whereas daily shows simply don’t have the time to do that. They rely on people being drawn into the story and wanting, needing, to find out what happens next. By episode 22 the savvy viewer had already figured out that Barnabas Collins was the vampire. Nobody had explicitly said so yet, however.

Maggie Evans, his favorite victim, has been “ill” in bed from loss of blood. Under Barnabas’ spell, she sends away her boyfriend and Victoria Winters—the original impetus for the entire series—has come to sit with her through the stormy night. As the two women argue about the proper care for Maggie’s condition, the storm continues, flashing lightning through the French doors in Maggie’s room. The wind blows the doors open and a flash of lightning shows the silhouette of Barnabas standing in the garden. I have to admit, even at my age and with my background of horror movie watching, that moment scared me. The genius of the show is that Barnabas is such a likable character. As the narrative develops, as it does beginning in episode 23, we come to see that Barnabas is a sad, reluctant monster. Perhaps if I’ve time enough, I should write a book about it. But then, I barely have a moment to squeeze in an episode now and again.