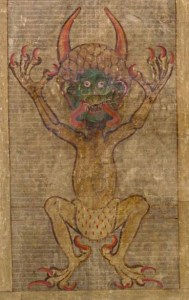

Jim was aghast. The joke had been entirely inappropriate. I had asked him about the Pentecostal service we’d just left. Jim was my college roommate and had invited me to see what his tradition was all about. I’d witnessed speaking in tongues before, but never on such a scale. That wasn’t what was bothering Jim, though. The minister had told a joke about a demon. It had something to do with a man possessed by a coffee demon. The exorcist declared to the demon “You have no grounds to be in him!” Inappropriate. It might make people think there weren’t real demons. We used to disagree on many points, but remained friends. I lost track of Jim. He dropped out of college to go follow a spirit-filled man in Waco who’d learned Hebrew and Greek without ever having studied them. His concern about that joke, however, raises an interesting question.

Jim was aghast. The joke had been entirely inappropriate. I had asked him about the Pentecostal service we’d just left. Jim was my college roommate and had invited me to see what his tradition was all about. I’d witnessed speaking in tongues before, but never on such a scale. That wasn’t what was bothering Jim, though. The minister had told a joke about a demon. It had something to do with a man possessed by a coffee demon. The exorcist declared to the demon “You have no grounds to be in him!” Inappropriate. It might make people think there weren’t real demons. We used to disagree on many points, but remained friends. I lost track of Jim. He dropped out of college to go follow a spirit-filled man in Waco who’d learned Hebrew and Greek without ever having studied them. His concern about that joke, however, raises an interesting question.

I’ve just finished reading Ralph Sarchie and Lisa Collier Cool’s book, Deliver Us from Evil: A New York Cop Investigates the Supernatural. It’s hard not to like Sarchie. A rough and tumble associate of Ed and Lorraine Warren, he is most sincere law enforcement officer (now, at my age, retired). Openly believing in the supernatural, claiming his traditionalist Catholic faith, he hates demons for the misery they cause both humans and God. I admire such unquestioning faith. At the same time he’s clearly aware of his own foibles and weaknesses—something we might like to see more often in the police force. He doesn’t doubt, however, that demons are real. The concern, however, is that he might sometimes be a bit harsh on non-Christian religions. He admits that he’s not the most studious of demonologists.

No doubt, belief is important. Belief with knowledge is even better, it stands to reason. Problem is, academic or scientific studies on demons are sorely lacking. Sarchie was an associate of the controversial Malachi Martin (whose book Hostage to the Devil I blogged about some time ago). I feel for someone who wants to know more but runs into the limits imposed by academia. Where do you find information if the recognized specialists in a discipline don’t write about it so regular people can read it? It is a real dilemma. A scientific approach would declare the events in Deliver Us from Evil (also published as Beware the Night, before being released as a movie) are anecdotal. This is technically correct. No laboratory procedure exists to confirm something science denies exists in the first place. The only weapon against such a foe is faith. Thinking back to college, I don’t know what happened to Jim, but on this point I’m sure he would have agreed.