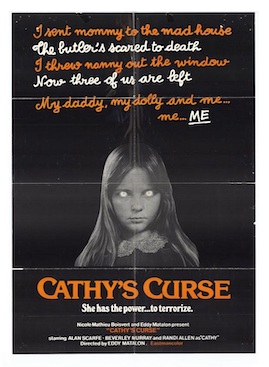

Learning to appreciate bad movies is a skill like any other. It takes practice. “Why?” I hear you ask? Why climb a mountain? Actually, there is a motive for seeing bad movies, apart from the good feeling they can leave you with. (I might’ve actually done it better!) That’s because they’re often free streaming. If I had an endless budget I might well be able to avoid bad movies, but what’s the fun in that? I found out about Cathy’s Curse because I was looking for a movie about a cursed doll. (Don’t ask.) I’ve seen many, of course. Child’s Play and the whole Annabelle series. But I felt I was missing something. Wikipedia actually has a page on haunted doll movies, and Cathy’s Curse stood out to me. Yes, I was forewarned, but I was also curious.

A Canadian horror film from 1977, Cathy’s Curse has become a cult classic. The story line decidedly makes no sense. Cathy, a young girl, moves into her grandparents’ house with her father and mother. Her father’s father had died in a car crash with his daughter Laura, about Cathy’s age, some 30 years earlier. Cathy’s parents are troubled, her mother having recently had a nervous breakdown. Laura’s vengeful spirit possesses Cathy through a doll the latter finds in the attic. For some reason, Cathy kills the housekeepers and attacks other children. She tries to drown herself. She kills the handyman’s dog. The dog, which is clearly male, is explicitly said to be female in the movie, perhaps because one of the favorite words of the writer is “bitch.” After about an hour and a half of running around screaming, the opening of the cursed doll’s eyes suddenly brings normalcy to the house.

There are some genuinely good things about the movie. The late fall-early winter mood is nicely framed. Why people hang out outdoors without coats in freezing weather is never really explained, though. Neither the writing nor the acting are stellar. And have I pointed out that the story makes no sense? But still, there’s something there. The idea of possession, a young girl under threat, the scary old mansion—these are classic tropes. It’s unclear why, when Cathy’s father is fixing breakfast, he immediately sends her to bed and it’s suddenly night. Or why the detective calls him by the wrong name. Or why nobody can take a doll away from a little girl. Ah, but that’s it, you see. The haunted doll. You have to learn how to appreciate these things, you know.