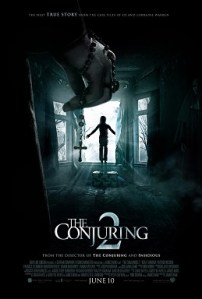

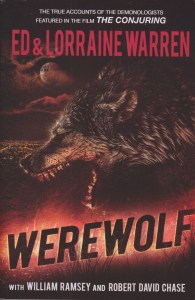

Although I don’t read movie reviews until after I’ve seen a film, I have a confession to make. With rumors swirling of The Conjuring 3, and since a chapter of Nightmares with the Bible will involve The Conjuring, I was a little curious what it might be about. Word on the street—and by “street” I mean “internet”—is that it will feature the case of Ed and Lorraine Warren that’s presented in Werewolf. Co-written by William Ramsey (the victim) and Robert David Chase, the book describes the strange malady of Ramsey, who never actually changed into a wolf, but for inexplicable reasons (at the time) thought himself a wolf and took on a wolfish look as he attacked people. The reports suggest he had preternatural strength at such times.

Although I don’t read movie reviews until after I’ve seen a film, I have a confession to make. With rumors swirling of The Conjuring 3, and since a chapter of Nightmares with the Bible will involve The Conjuring, I was a little curious what it might be about. Word on the street—and by “street” I mean “internet”—is that it will feature the case of Ed and Lorraine Warren that’s presented in Werewolf. Co-written by William Ramsey (the victim) and Robert David Chase, the book describes the strange malady of Ramsey, who never actually changed into a wolf, but for inexplicable reasons (at the time) thought himself a wolf and took on a wolfish look as he attacked people. The reports suggest he had preternatural strength at such times.

Since most of the Warrens’ books are concerned with demons, it should come as no surprise that in this case that was the diagnosis as well. With no real reason given, once upon a childhood evening Ramsey was possessed and occasionally broke out into violent fits. He landed in a psychiatric hospital a couple of times, but was eventually released. Noticed by the Warrens on one of their trips to England, Ramsey was invited to come stateside for an exorcism. According to the book, the rite was successful at least up until the time of publication. That’s the thing about demons—you can’t always tell for sure when they’re gone.

It’s pretty obvious why such a story line would appeal for a horror flick. You’ve got a werewolf, an unnamed demon, and an exorcism—there’s a lot to work with here. Weird things happen in the world, and there’s not too much to strain the credulity in this case. It would seem possible that a mental illness could cause much of what’s described as plaguing Ramsey, though. Its episodic nature is strange, I suppose, and the Warrens had a reputation for spotting demons. I did miss the conventional elements of the exorcism, however. No demon forced to give its name, no levitating and no head-spinning. Not even a bona fide bodily transformation. They’ll be able to fix that in Hollywood, I’m sure. Credulous or not, there will always be people like me who feel compelled to read such books. And since there’s no final arbiter but opinion in cases of the supernatural, that can leave you wondering.