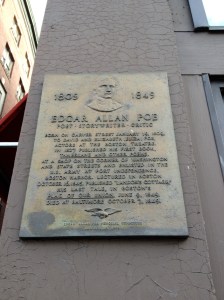

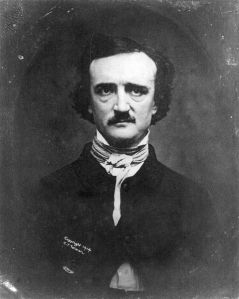

In my mind, Baltimore is inextricably bound to Edgar Allan Poe. From the accounts of Poe’s life, it is clear that he sensed nowhere as a welcoming home. Indeed, he was barely mourned at his passing and the memorial gravestone in this city was only added decades later when his works had attracted serious attention. Many of the eastern cities now like to claim him: Boston (although with Bostonian diffidence), New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Richmond. All have various mementoes of his transient existence in those places, although he was not made to feel at home there when he was actually alive. The writing life is a difficult and often lonely one. Poe knew that better than many. It is so lonely that nobody is even sure why he was in Baltimore when he died, or what the cause of death was. He has become an icon to many that write.

Ironically, my career has repeatedly shoved me back to the publishing industry. That doesn’t mean that it is any easier to get published, however. The world is full of words, and those who hold the key to publishing respectability have so little time (a fact I know well, as a sometime editor). Some of us resort to blogs and pseudonyms while others die young in Baltimore. The world loves a self-promoter. Those with something intelligent to say are often discovered only in retrospect. And soon their work enters the public domain and can be claimed by all.

Other writers have called Baltimore home. Not many have football franchises named after their literary works, whether here in Maryland or elsewhere. And Baltimore, like many of the major cities of the United States, has great swaths of the neglected, the poverty-bound, and the hopeless. As I drive through the city it is clear that many have been left to face the cruelties of a self-promoters’ economy. They live with little—overlooked and forgotten. But there’s a party in town for those who can afford it. As I settle down with a cask of Amontillado and my notebook, I know that I have only just begun to get to know Baltimore. Maybe I will meet the ghost of Poe here, amid the brightest lights of scholarship and the darker shadows beneath.