Dark academia is the new gothic. It’s all the rage on the internet, as I found out by releasing a YouTube video on the topic that quickly became my most popular. Still, I was surprised and flattered when Rent. asked me my opinion on the dark academia aesthetic. You should check out their article here. What drew me to dark academia is having lived it. Although the conservatism often rubbed me the wrong way, Nashotah House was a gothic institution with skeletons in closets and ghosts in the corridors. Tales of hauntings were rife and something about living on a campus isolated from civilization lends itself to abuses. An on-campus cemetery. Even the focus on chapel and confession of sins implied much had to be forgiven. The things we do to each other in the name of a “pure” theology. Lives wrecked. And then hidden.

I entered all of this naive and with the eagerness of a puppy. I was Episcopalian and I had attended the pensive and powerful masses at the Church of the Advent on Beacon Hill in Boston. I was open to the mystery and possibilities even as I could see the danger in the dogmatic stares of the trustees. It was a wooded campus on the shores of a small lake. A lake upon which, after I left, one of the professors drowned in a sudden windstorm. I awoke during thunderstorms so fierce that I was certain the stone walls of the Fort would not hold up. Disused chapels full of dead black flies. Secret meetings to remove those who wouldn’t lock step. This was the stuff of a P. D. James novel. Students at the time even called it Hogwarts. They decided I was the master of Ravenclaw.

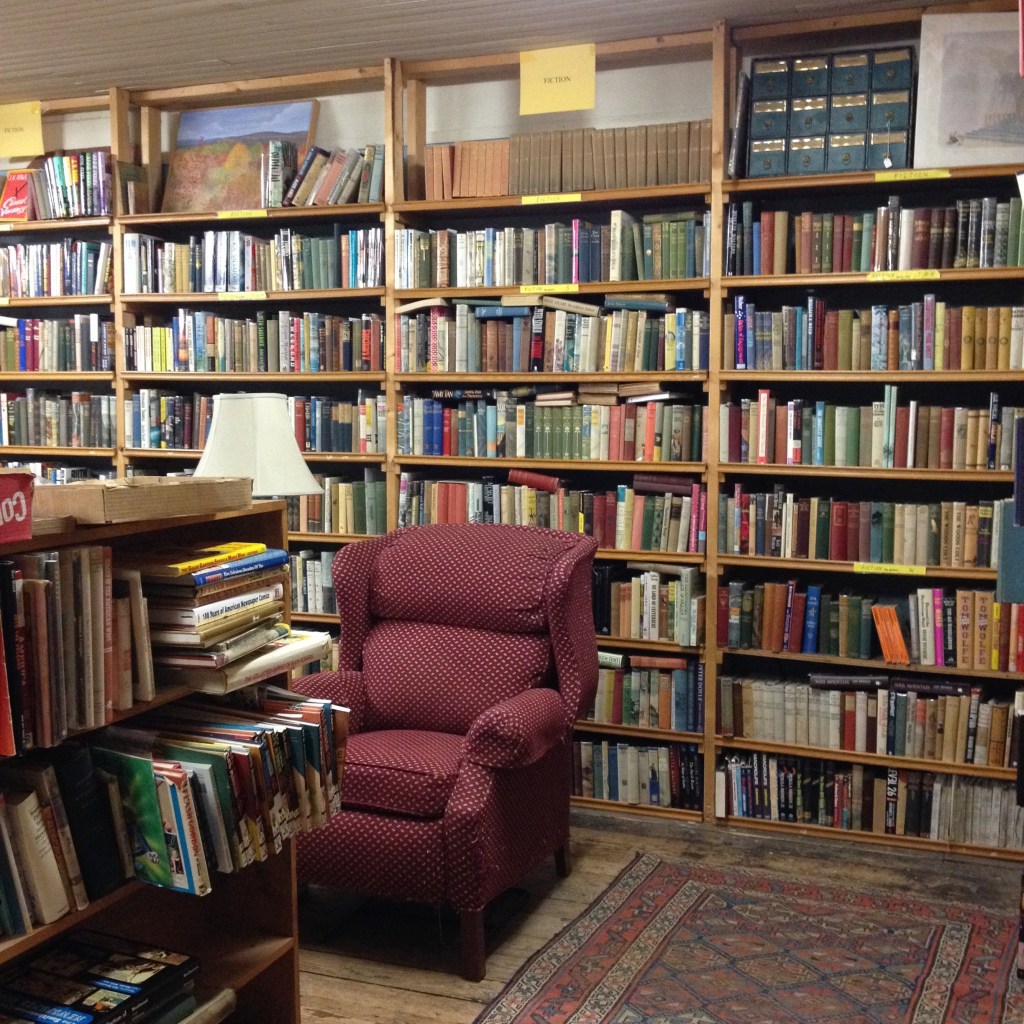

Fourteen years of my life were spent there. I worked away at research and writing in my book-lined study painted burgundy. Is it any wonder that I find dark academia compelling? I’ve often written, when discussing horror films on this blog, that gothic stories are my favorites. Even the modern research university can participate. Professors, isolated and often unaware of what’s happening outside their specializations, still prefer print books and a nice chair in which to read them. And, of course, I’d read for my doctorate in Edinburgh, one of the gothic capitals of Europe. Even Grove City College had its share of dark corners and well-kept secrets. What goes on in that rarified atmosphere known as a college campus? The possibilities are endless. On a stormy night you can feel it in your very soul.

That article again: Dark Academia Room Decor: Aesthetic Secrets Revealed