When I travel, when I have time to plan, I like to visit the haunts of literary figures. It would be difficult to think of two more influential (or abbreviation-ridden) English writers than J. R. R. Tolkien and C. S. Lewis. Both Oxford men, they liked to drink, I believe, at the Lamb and Flag. I stopped by to see, but just in case it was actually the Eagle and Child, I back-tracked to see it as well. Post-war Oxford was a place for an academic to write, and C. S. Lewis has influenced an entire generation of evangelical fans who overlook his penchant for drinking, and J. R. R. Tolkien seems to have invented the perfect fodder for CGI animators. Perhaps there was something in the air. Although no less of a literary talent, it may be less common to hear Thomas Hardy’s name. He is rumored to have written Jude the Obscure, appropriately, mostly in this pub. Good to know there’s someone else so obscure, by definition. It’s hard not to feel scholarly in Oxford.

I have to confess, I dressed the part. I wore my Harris Tweed jacket and my Edinburgh school tie. It was a beautiful spring day, the like of which were extremely rare in Scotland some two decades ago. Not knowing that my business trip would offer the opportunities to explore the city a little, I hadn’t done much homework. A colleague suggested I stop into St. John’s College to look at the gardens. They’re only open from 1 to 5, and I timed it right to get there shortly before closing. Students wandering out in jeans, staring at their smartphones, could have been students at any number of universities I’ve known. The setting was, however, quite beautiful. There seems to be evidence that they don’t walk on the lawn. Tradition is treated with considerable respect here. Although, upon closer look, graffiti does make an appearance now and again.

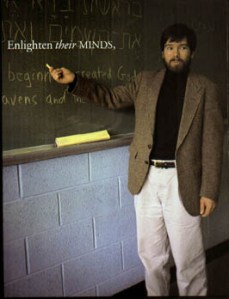

As I was stepping out the door of St. John’s, a family from eastern Asia was coming in. It was near closing time. The father asked me if this was Oxford University. I explained that it was part of Oxford University, but that the university was quite large and was all around the town. As he pressed me for more information, I wondered why he was asking an American who’d only been to Oxford once before about the place; I hadn’t done my homework, after all. Then it occurred to me. I was dressed rather like a prototypical professor. The tweed, the beard, the glasses, the consistently confused look on my face—I’d been mistaken for an university professor. I stepped outside and looked around. In a different time, perhaps it would have been true. And maybe Tolkien and Lewis would have lifted a warm pint in a cold pub and we all might have learned something.