One of the realities of being an editor is that you have authors consistently ignore your advice and then ask you for solutions when what you predicted would happen does. Oh, that sentence! Let me put it this way: there used to be a time when simultaneous submission was frowned upon. Even “forbidden” by some publishers. The internet has changed all that. Publishers who won’t accept submissions if anyone else is also considering them, lose out. There are lots of publishers out there. Many more than most people think. Some of them are small and fly-by-night, but others are also ultra-specialized so they can hit their markets. Even among academic publishers there are many to choose from. If you submit to only one, wait to hear, and then get a “no,” you have to start all over again. Or submit simultaneously.

Peer review can take a long time. I mean a l-o-n-g time. Especially since the pandemic, but even before, overwrought academics have trouble committing to adding one more thing to their plates. If they do accept a review offer, the response is likely to be quite late; more often after the deadline than before. I’ve been an anxious author waiting. It’s the kind of limbo few actually enjoy. It’s a reality, however. If your book is about current events, or something trending, well, godspeed. That’s a tough place to be. Submitting to more than one publisher at a time gives you the leg up of not losing time if someone turns you down. Some authors prefer a certain publisher and want to hold out for them. Publishers get lots of proposals. If I had so many proposals when I was in college I wouldn’t have been nearly so lonely. Holding out is bad dating advice.

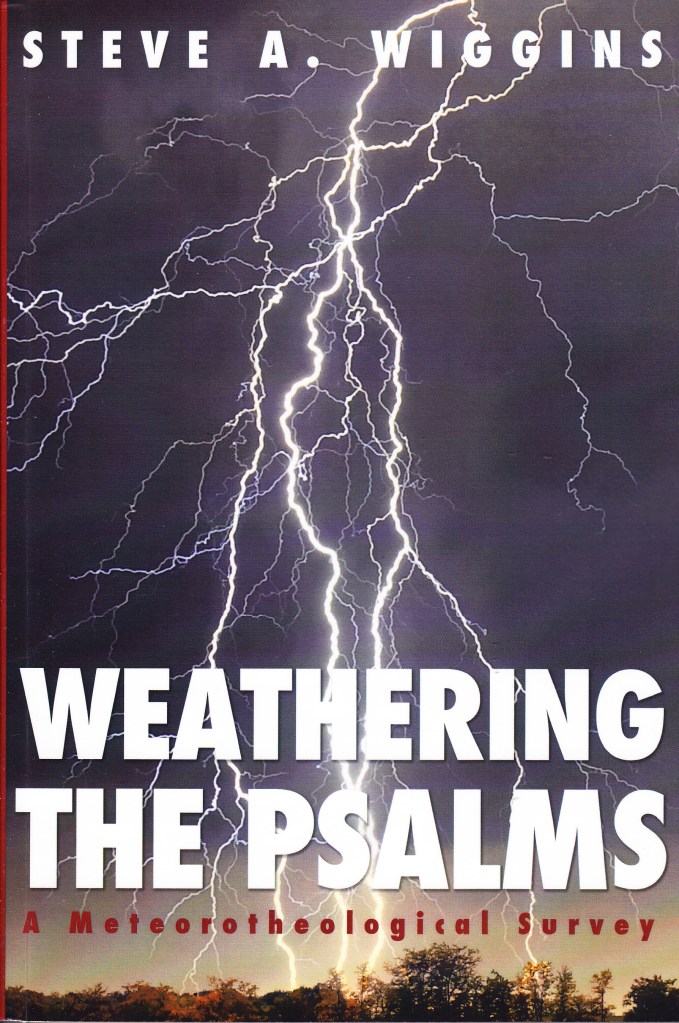

The best piece of editorial advice I can muster is to research publishers. Academics are researchers by nature, but few take the time to research publishers. There’s plenty of information out there. When I couldn’t get an agent interested in Holy Horror, I turned to McFarland. Why? Because I’d familiarized myself with the kinds of books they publish and mine seemed a good fit for them. Sure, there were more prestigious places to go, but I’m a bit too busy to bang my head against that wall all day. Even a little bit of web searching on publishers can pay off. Publishing is a business. Never forget that. If you only want to get your ideas out there, starting a website (which isn’t expensive) is probably a better way than getting a book published. Writing books is great, and getting them published is incredibly validating. But do yourself a favor, if your editor suggests a course of action to you, take it.