From my youngest days I remember wanting to be a scientist. This desire was tempered with a real fear of Hell and wish to please. In my career, it seems, the latter won out. Well, mostly. I never planned on being an editor, but it was clear that I missed the hard-core science courses and would always lack scientific credibility. You see, I believed what scientists said, and that included science teachers in high school. To this day I still believe in the back of my mind that you can’t really see atoms with a microscope. One of my teachers had said it was impossible, and although electron microscopes were still a long way off, it was clear that atoms were just too small. The force of materialism first hit me in ninth grade physics. If what I was hearing was true, then if you had enough information, you could figure out the whole universe. But what of Hell?

From my youngest days I remember wanting to be a scientist. This desire was tempered with a real fear of Hell and wish to please. In my career, it seems, the latter won out. Well, mostly. I never planned on being an editor, but it was clear that I missed the hard-core science courses and would always lack scientific credibility. You see, I believed what scientists said, and that included science teachers in high school. To this day I still believe in the back of my mind that you can’t really see atoms with a microscope. One of my teachers had said it was impossible, and although electron microscopes were still a long way off, it was clear that atoms were just too small. The force of materialism first hit me in ninth grade physics. If what I was hearing was true, then if you had enough information, you could figure out the whole universe. But what of Hell?

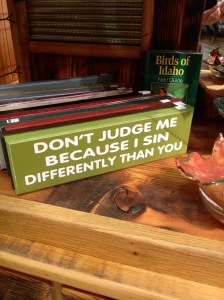

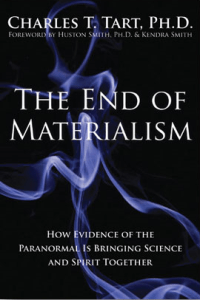

I read Charles T. Tart’s The End of Materialism because of my need for reassurance. Materialism leaves me cold. To find a scientist who feels the same way is a bonus. Not all authorities agree that we’re just excited atoms that can be seen. Tart is willing to consider the spiritual as part of what the evidence reveals. He explores it in the context of psi rather than in the doomed attempt to test religions empirically, but he does make a case for more to this universe than Horatio’s philosophy ever dared dream. And some of that more is decidedly not physical. It’s what we know from our experience of the world. We don’t only reason, we also feel. I have to wonder if reason is really the friend of materialism after all.

You can’t walk across Manhattan without seeing an ambulance most days. Often they’re called out to collect some unfortunate homeless person who collapses from our collective neglect. If we are only matter, then why do we bother to assist those in distress? It’s just a little electricity and some chemicals in a biological organ, right? Consciousness is only an illusion, after all. Unless, of course, the person suffering is a prominent scientist. Then we should all make way for the ambulance lest we lose an asset of great value. Materialism is insidious in its take-no-captives mentality. Feel what you will, there’s nothing more to life than physical stuff. You can make a good living believing that. Why is it that I’m suddenly thinking of Hell again?