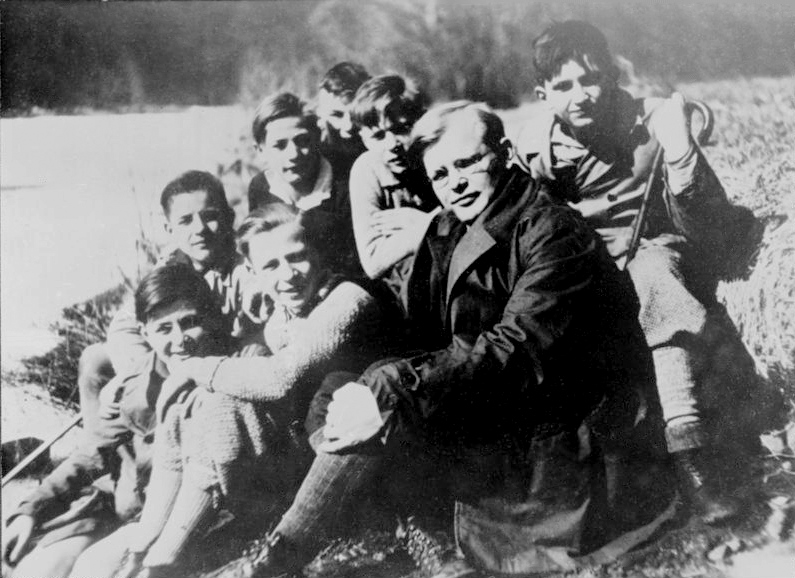

Dietrich Bonhoeffer was a certified evangelical Christian. His theology often feels a bit pat to some of us who work in religious studies, but there’s no doubt that Bonhoeffer was a brilliant man. Bonhoeffer believed in Jesus but resisted Hitler. In fact, that resistance cost him his life. My brother recently sent me a Facebook Reels video on Bonhoeffer’s observations about stupidity, which Bonhoeffer believed was far more dangerous than evil. I shared that video in my feed on Facebook yesterday, and it is well worth listening to. Stupidity isn’t a badge most people would wear proudly. We all do wear it from time to time since we’re only human. The real problem, according to Bonhoeffer, is when crowds start becoming stupid. We’ve seen it time and again. We’re living in such a time right now. The antics coming out of DC right now have thinking people everywhere wondering how this is even possible. Listen to Bonhoeffer.

I don’t take Bonhoeffer uncritically. Some of us—generally without tons of friends—think critically by default. (The women in college all broke up with me because “You’re too intense.” I credit my wife with sticking with me, although she tells me they were right.) Anyone can learn critical thinking. The problem is, keeping the skill is hard work. And the internet doesn’t help. Whenever anyone makes a claim, personally, my default response is “How do they know?” Yes, I do look up references. With my particular brand of neurodivergence, I seldom trust other people to know something unless they’re experts. (This is something the current administration is a bit shy on.) I even question experts if their conclusions look suspect. “Nullius in verba” is written in my academic notebooks. Something, however, is obviously clear. Bonhoeffer was right about stupidity.

I’m not sure what an unfluencer like myself hopes to gain by discussing this. I do hope that folks will listen to Bonhoeffer if they have concerns about my thought process. My deeper concern is that the church often encourages stupidity. Unquestioning adherence to something the facts expose as untrue is often lauded. It makes some people saints. Churches require followers and often distrust critical thinkers. That once cost me my job, sending my career into a tailspin. This was well pre-Trump, but some in authority didn’t appreciate critical thinking on the part of faculty. (Ahem, that’s what we’re paid to do). I’m not anti-belief. Anyone who really knows me knows that I believe very deeply in the immaterial world. And I know that Bonhoeffer did too, right up to the gallows.