In a move that threatens intellectual whiplash, the Kansas State Board of Education has backed the Next Generation Science Standards. For a state historically at war with evolution, adopting a curriculum that (rightly) presents evolution and global warming as facts, there is cause for hope. As an average citizen sometimes just struggling to get by, I watch in stunned horror as our elected officials try to repeal Obamacare without touching their own health plans paid for by yours truly (and mine truly). I see them vote themselves pay raises while pension plans and salaries of ordinary citizens are frozen. I know where the buck actually does stop. So it is strangely encouraging to see a state that has declared war on science beginning to realize that yes, the truth does have consequences.

Science does not necessarily have all the answers, but it is the best that we know. The empirical method works, and our healthcare, transportation, and communication have all benefited enormously by it. Our way of life has grown easier because of our application of evolution and its ways to our understanding of microbes and the ways to hold off their attacks. Science has been warning us since I was a high schooler, over three decades ago, that our industrialization has been causing grave changes to our ecosystem. Unfortunately, those with money to make from it can simply afford to move to higher ground. Kansas is among the Great Plains states. It is wise to recognize that global warming threatens those who live close to the earth most of all.

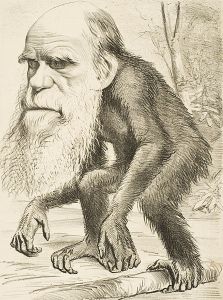

The intolerance to science is not simply a religious reaction, as some would characterize it. Religion may be used in the interest of business. And any savvy entrepreneur knows, and exploits that fact. It matters not a jot or tittle if you evolved from a common ancestor with the apes, as long as you can climb, like King Kong, to the highest towers and look down on all the rest of humanity. The water from melting ice caps may be rising below, but the Great Ape need not worry. Until it becomes clear that without the little guys down below, even the top monkey is nobody.