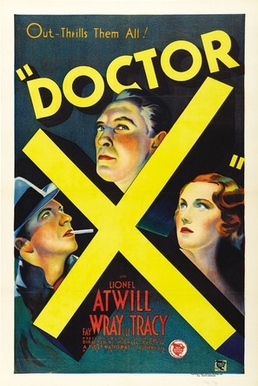

One of the early horror movies not in the Universal lineup was Doctor X. It deals with themes that are perhaps surprising to modern viewers of old movies since the Motion Picture Production Code had not yet taken effect. The story itself is slow paced, as is typical for the time, and not very scary according to modern standards. Police are investigating a series of full moon killings and have traced them near to Dr. Xavier’s institution, the Academy of Surgical Research. There he, along with four other scientists, are conducting advanced, but unorthodox medicine. Dr. X convinces the police that he will investigate thoroughly and if the killer is among his colleagues, which he does not believe he is, he’ll learn which one. There’s quite a bit of screwball humor introduced by the investigative reporter and even the butler and maid. Hooking everyone up to a machine that indicates excitement, Dr. X has the murder reenacted to determine guilt among the watching scientists. This is an early form of polygraph, apparently.

One of the colleagues, Dr. Wells, is excused because he is missing a hand and the murderer clearly used two. The lights go out during the experiment and the “guilty” doctor is found murdered. The solution Dr. X proposes is to do the experiment again, using his daughter (with whom the reporter has fallen in love) as the “victim.” In order to prevent anyone from moving around, all but Wells are handcuffed to their chairs that are bolted to the floor. Wells is then shown transforming himself into a monster by using “synthetic flesh” that he’s developed, allowing himself to animate a second hand and also, to disguise his face, freeing him from being identified. He attacks Dr. X’s daughter, but the scientists are all handcuffed to their chairs. The comic reporter saves the day by destroying the monster.

These early horror films blazed trails for later monster movies. The science is a mix of plausible sounding theory and mumbo-jumbo. I wasn’t sure what to expect since I knew the movie by name only. Dr. X is a kind of mad scientist, but he’s not evil. There’s a theme of cannibalism that runs through the story as well, since this is where Wells gets the material for his synthetic flesh. The themes are scarier than what’s shown on the screen, of course. These were the days when Boris Karloff in Frankenstein monster makeup could cause viewers to faint. Doctor X was never as popular as the Universal lineup and although Wells is grotesque enough, he’s no Frankenstein creature. He is, however, part of cinematic monster history.