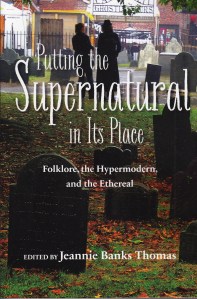

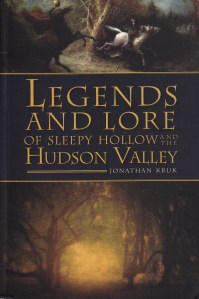

Local history has always been an interest of mine. Although I’ve never lived in Sleepy Hollow, my book on “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” is due out this week. I try to keep an eye out for further information on the region. Christopher Skelly’s The Origin of Sleepy Hollow: The Name and the Village, an Untold History appeared after I’d submitted my manuscript to McFarland, but I wanted to read it regardless. A new father living in Wisconsin at the time, I was not aware of the name change in 1996. I do remember looking at a map after we’d moved to New Jersey and seeing, for the first time, the name Sleepy Hollow along a route we planned to take to a point further up the Hudson. I remember thinking, “I didn’t know there was an actual place called Sleepy Hollow.” Well, that may have been because prior to 1996, there wasn’t.

This self-published account of how the name came about is valuable local history. Not exactly belles-lettres, it nevertheless begins at the earliest Dutch naming of the area as the Dutch version of Sleepy Hollow. By the time Washington Irving wrote his story around 1819, the area had already gone by several names but the village of Tarrytown was well established. And, over time what was vaguely called Sleepy Hollow by the Dutch became North Tarrytown. I learned here that the haven, or harbor on the Tappan Zee that was first called some version of “Sleepy” had been the victim of landfill so that a railroad could be put in. The author is clear that the “Hollow” is still visible if you know where to stand and look. He also explains the motivations behind changing the village name that began in 1988.

One things I learned in my own study of ancient history is that place names tend to be remarkably resilient. European settlers ignored much of the indigenous nomenclature, but did adapt many examples of it. Our species needs to reference where things, or other people, are over very large distances. We know where Edinburgh is, even if we live in Australia. Names are important. Personally, I’m glad that some citizens of North Tarrytown decided to change the name of their village to Sleepy Hollow. And not just because I have a book coming out on the topic. I’m sure the change has boosted tourism immensely, even if that wasn’t the initial motivation. It’s nice to know that the change was actually back to the first Dutch ideas about the place. And that a visit to Sleepy Hollow is possible because of one influential little story.