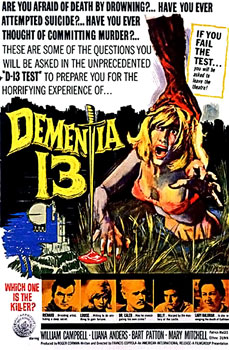

Dementia 13 is a strange little movie. It’s Francis Ford Coppola’s directorial debut, and it was produced by Roger Corman and released by American International Pictures. Like many Corman/AIP movies, it was low budget and quick. It seems that Corman had some money left over in the budget from a previous movie and he offered Coppola the opportunity to direct a film shot quickly and funded by the leftover funds. With a script written in three days (and it shows), he set out to film what was intended to be a Psycho knock-off. The title might give that away, although I’m not sure what the 13 has to do with it, other than being “unlucky.” Shot in Ireland with mostly American actors, the film is suitably gothic, but the original start to the movie is a red herring. So what’s it about?

A rich heiress has never recovered from the death of her young daughter, who drowned in the rather sizable pond on the estate. One of her three sons dies early in the film, setting up a subplot that goes nowhere. The two remaining sons, unaware of their brother’s death, keep the ritual of the annual acting out the sister’s funeral. While the widow of the deceased son tries to work her way into the will, she is axe-murdered, bringing this into the horror genre. The family doctor suspects something’s wrong (although viewers are led to suspect him), and finally solves the crime after another bit character is beheaded. Part of the problem is the film is too brief to develop the ideas properly. Released at only 80 minutes, with a 5-minute gimmicky prologue, you really don’t have time to absorb the psychology of the characters.

The influence of Psycho is pretty obvious, the wet woman slowly chopped to death while in the water, is the scariest scene in the movie. It’s shot in such a way that it’s not obvious that she’s actually being struck until the end of the act (a budget thing, I suspect). The wealthy widow drops out of the story as the family doctor becomes the self-appointed detective. Of course, the previous deaths have been undetected, so no actual police come. In sum, creepy (but not too creepy) Irish castle, siblings working at cross-purposes, a scheming daughter-in-law, and the irruption of the past into the present, along with the black-and-white filming, ofter a quick gothic thrill. Otherwise, it seems more like homework than an example of foundational horror, but still, it has had inspired a remake, and that’s saying something for a three-day script.